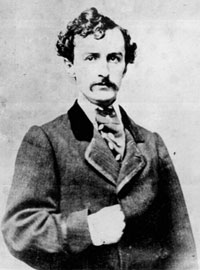

John Wilkes Booth (1838-1865)

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838 April 26, 1865) was an American actor who is most famous for assassinating Abraham Lincoln. A professional and extremely popular stage actor of his day, Booth was a Confederate sympathizer who was dissatisfied by the outcome of the American Civil War.

Background and early life

Booth was born on a farm near Bel Air, Harford County, Maryland. His parents, Junius Brutus Booth and Mary Ann Holmes, were British and had moved to the United States in 1821. He was named after the famous British revolutionary John Wilkes, whom the family claimed as a distant relative; Junius himself was named after the legendary Roman statesman Marcus Junius Brutus, one of the assassins of Julius Caesar. Junius was one of the most famous actors on the American stage; he also had a reputation as an eccentric and a drunk, even insane. After he died in 1852 the poet Walt Whitman wrote, "There went the greatest and by far the most noble Roman of them all." Booth's brother, Edwin Booth, was the most influential Shakespearean actor in America in the late 19th Century. Another brother, Junius Booth, also followed their father into acting.

Booth appeared to have led a happy childhood. He received an education in the classics and in particular Shakespeare. In 1851 Booth attended St. Timothy's Military Academy near Baltimore. It was there that he met Samuel Arnold and Michael O'Laughlen, both of whom would later become involved in Booth's attempt to kidnap and, later, murder Lincoln.

Theatrical career and Civil War

Booth made his stage debut in August, 1855, at the age of 17, when he played the Earl of Richmond in Shakespeare's Richard III. At his request he was billed as "J.B. Wilkes", a pseudonym meant to divert attention away from his famous thespian family. In 1858 he became a member of the Richmond Theatre, and his career started to take off. He was referred to in reviews as "the handsomest man in America." He stood 5 feet, 8 inches tall, had jet-black hair, and was lean and athletic. He was also an excellent swordsman. His performances were often characterized by his contemporaries as acrobatic and intensely physical. A fellow actress once recalled that he occasionally cut himself with his own sword, and routinely slept covered in steaks to tend to the bruises inflicted on the stage.

In 1859, Booth happened to be preparing for a theatrical engagement in Richmond, Virginia, a few weeks before the scheduled execution of the famous abolitionist John Brown. In October, Brown had raided the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (in present-day West Virginia) in an unsuccessful attempt to start a state-wide slave insurrection. Upon hearing of the verdict, Booth headed to Charles Town, bought a Richmond Gray militia uniform from state officers, and stood guard along the gallows as Brown was hanged.

When Abraham Lincoln was elected president on November 6, 1860, Booth wrote a long speech that decried what he saw as a Northern abolitionism and made clear his strong support of the South and the institution of slavery. On April 12, 1861, the Civil War broke out, and eventually 11 Southern states seceded from the Union. Booth's family was from Maryland, a border state which remained loyal to the Union during the war despite a slaveholding population that was strongly sympathetic to the Southern cause. Along with the fact that Maryland shared a border with Washington, D.C., Lincoln had declared martial law in the state, a view that many, including Booth, viewed as unconstitutional and an abuse of executive power.

Booth, like many in Maryland, came from a divided family. Most of his family were staunch Unionists, but Booth considered himself a Southerner, and he made an early promise to his mother that he would not enlist in the Confederate Army. Instead he lived out the war mostly in Washington D.C., travelling North and South as a performer and as far west as Ohio. Booth was outspoken in his love for the South, and equally outspoken in his hatred for Lincoln. In early 1862, Booth was arrested and taken before a provost marshal in St. Louis for making anti-government remarks.

Booth and Lincoln crossed paths on several occasions. Lincoln was an avid theater-goer and especially loved Shakespeare. On November 9, 1863, President Lincoln saw Booth playing Raphael in Charles Selby's The Marble Heart at Ford's Theater in Washington. At one point during the performance, Booth shook his finger in Lincoln's direction as he delivered a line of dialogue. Later, Lincoln requested to meet the actor after the play but Booth refused. Ironically, Lincoln sat in the same "presidential box" in which he would later be assassinated. Booth made only one other acting appearance at Ford's. That occurred on March 18, 1865, when he played Duke Pescara in The Apostate in what was the last appearance of his career. However, Booth's family was long time friends with John T. Ford, the theater's owner, and Booth was in and out of the theater so often during the war that he even had his mail sent there. This granted Booth complete access to Ford's Theater, day and night.

Hatching the plot

By 1864, the tide of the war had shifted in the North's favor. The North halted prisoner exchange in an attempt to dwindle the size of the Confederate Army. Booth began devising a plan to kidnap Lincoln from his summer residence at The Soldier's Home outside of Washington, smuggle him across the Potomac and into Richmond. He would be exchanged for the release of Southern soldiers held captive in Northern prisons. He successfully recruited his old friends Samuel Arnold and Michael O'Laughlin as accomplices. At this time, Booth had been also speculating in oil in Pennsylvania.

Possible ties to the Confederacy

In the summer of 1864, Booth met with several well-known Confederate sympathizers at The Parker House in Boston. In October 1864 he made an unexplained trip to Montreal. At the time, Montreal was a well known center of clandestine Confederate activities. It is known that he spent ten days in the city and stayed for a time at St. Lawrence Hall, a meeting place for the Confederate Secret Service, and met at least one blockade runner there. It is possible that it was here that he also met George Nicholas Sanders, a one-time government official with revolutionary sentiments who had once called for the assassination of Napoleon III. There has been much scholarly attention devoted to why Booth was in Montreal at this time, and what he was doing there. No solid evidence has ever linked Booth's kidnapping or assassination plot to a conspiracy involving any elements of the Confederate government. In her memoir of her brother, The Unlocked Book, Asia Booth Clarke later attested that Booth told her he was a blockade-runner for the South, and also smuggled quinine across the Potomac. These allegations have likewise never been proven.

The kidnapping attempt

Booth began to devote more and more of his energies and finance to his plot to kidnap Abraham Lincoln after his reelection in early November, 1864. He assembled a loose-knit band of Southern sympathizers, including David Herold, George Atzerodt, John Surratt, and the giant Confederate deserter, Lewis Payne. They began to meet routinely at the boarding-house of Surratt's mother, Mary Surratt.

On November 25, 1864, John Wilkes performed for the first and only time with his two brothers, Edwin and Junius, in a single engagement production of Julius Caesar at the Winter Garden Theater in New York. The proceeds went towards a statue of William Shakespeare for Central Park which still stands today. The performance was interrupted by a failed attempt by clandestine Confederate forces to burn down several hotels, and by extent the city, with Greek Fire. One of the hotels was next door to the theater but the fire was quickly extinguished. The following morning, Booth argued bitterly with Edwin about Lincoln and the war.

The following year, Booth attended Lincoln's second inauguration on March 4, 1865 as the invited guest of his secret fiancée Lucy Hale (Lucy's father John P. Hale was Lincoln's minister to Spain). In the crowds below were Powell, Atzerodt, and Herold. There seems to have been no attempt to kidnap or assassinate Lincoln during the inauguration. Later, however, Booth remarked about "what a wonderful chance" he had to shoot Lincoln had he so chosen.

On March 17, Booth learned at the last minute that Lincoln would be attending a performance of the play "Still Waters Run Deep" at a hospital near the Soldier's Home. Booth rounded up his team on a stretch of road near the Soldier's Home in the attempt to kidnap Lincoln en route to the hospital, but the president never showed. Booth later learned that the President had changed plans at the last moment to attend a reception at the National Hotel in Washington, which ironically was where Booth lived.

The assassination

On April 10, after hearing the news that Robert E. Lee had surrendered at Appomattox, Booth told a friend, Lou Weichmann, that he was done with the stage, and that the only play he wanted to present henceforth was Venice Preserv'd. Although Mr. Weichmann didn't understand the reference, Venice Preserv'd is about an assassination plot.

On April 11, Booth was in the crowd outside the White House when Lincoln gave an impromptu speech from his window. When Lincoln stated that he was in favor of granting suffrage to African-Americans, Booth turned to Lewis Powell and urged him to shoot the president on the spot. Powell refused. Booth claimed that it would be the last speech Lincoln would ever make.

On the morning of Good Friday, April 14, 1865, Booth heard that the president and Mrs. Lincoln, along with General Ulysses S. Grant and his wife, would be attending the play Our American Cousin at Ford's Theater. Booth immediately set about making plans for the assassination and an escape route. Later that night, Booth informed Powell, Herold and Atzerodt of his intention to kill Lincoln. He assigned Powell to assassinate Secretary of State William Seward and Atzerodt to assassinate Vice-President Andrew Johnson. Herold would assist in their escape into Southern territory. By targeting the President and his two constitutional successors to the office, Booth seems to have intended to decapitate the Union government and throw it into a state of panic and confusion. With any hope, the Confederate government could then reorganize and continue the war.

Booth, who as a famous actor and friend of owner John Ford had free access to all parts of the theater, snuck into Lincoln's box and shot him fatally in the back of the head with a .44 caliber Deringer pistol.

Booth then jumped out of the President's box and fell to the stage, reportedly breaking his leg. Many historians now believe, however, that Booth actually broke his leg when his horse fell on him later in the escape, and that the "diary" entry claiming it occurred jumping to the stage is a typical Booth dramatization. Some witnesses said he shouted "Sic semper tyrannis" from the stage, while others said he shouted "The South is avenged." He fled to the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd, who treated the broken leg. Mudd was later sentenced to life at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas, but released early for his efforts in stemming a yellow fever epidemic. Ironically, one of the other plotters and fellow prisoners, whom he took into his care when he returned home, survived him.

Booth was pursued by Union soldiers through Southern Maryland and across the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers to Richard Garrett's farm, near Bowling Green, Caroline County, Virginia. Early in the morning of April 26, 1865, the soldiers caught up with Booth. Trapped in a tobacco barn, Booth refused to surrender and the soldiers set the barn ablaze. Sergeant Boston Corbett, against orders, fired at Booth and fatally wounded him in the neck. Booth was dragged from the fire and he died on the porch of the farmhouse. His last words were spoken as he stared at his hands and reportedly muttered, "Useless! Useless!"

Booth's body was taken to the Washington Navy Yard for identification and an autopsy. The body was then buried in a cell in the Old Penitentiary at the Washington Arsenal. In 1867, the body was exhumed, placed in a pine box, and locked in a warehouse at the prison. In 1869, the body was once again identified before being released to the Booth family, where it was buried in a family plot at Greenmount Cemetery in Baltimore.