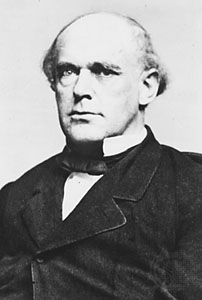

Salmon P. Chase (1808-1873)

Salmon Portland Chase (January 13, 1808 - May 7, 1873) was a lawyer and politician, antislavery leader before the U.S. Civil War, secretary of the Treasury (1861-64) in Pres. Abraham Lincoln's wartime Cabinet, sixth chief justice of the United States (1864-73), and repeatedly a seeker of the presidency.

Chase was born in Cornish, New Hampshire, and lost his father when he was nine years old. He was raised and educated by his uncle, Bishop Philander Chase, the first Episcopal bishop of Ohio and later of Illinois. He studied in the common schools of Windsor, Vermont, Worthington, Ohio, and at the Cincinnati College, and graduated from Dartmouth College in 1826. He studied under U.S. Attorney General William Wirt (1827-30) and was admitted to the bar

Chase was born in Cornish, New Hampshire, and lost his father when he was nine years old. He was raised and educated by his uncle, Bishop Philander Chase, the first Episcopal bishop of Ohio and later of Illinois. He studied in the common schools of Windsor, Vermont, Worthington, Ohio, and at the Cincinnati College, and graduated from Dartmouth College in 1826. He studied under U.S. Attorney General William Wirt (1827-30) and was admitted to the bar

From 1830 he practiced law in Cincinnati, Ohio, where he became widely known for his courtroom work on behalf of runaway slaves and white persons who had aided them. He soon gained a position of prominence at the bar, and published an annotated edition, which long remained standard, of the laws of Ohio. At a time when public opinion in Cincinnati was largely dominated by Southern business connections, Chase, influenced probably by James G. Birney, associated himself after about 1836 with the anti-slavery movement, and became recognized as the leader of the political reformers as opposed to the Garrisonian abolitionist movement. From his defense of escaped slaves seized in Ohio for rendition to slavery (under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793) he was dubbed the Attorney General for Fugitive Slaves. His argument in the famous Van Zandt case before the United States Supreme Court attracted particular attention, though in this as in other cases of the kind the judgment was against him. In brief, he contended that slavery was local, not national, that it could exist only by virtue of positive state law, that the federal government was not empowered by the U.S. Constitution to create slavery anywhere, and that when a slave leaves the jurisdiction of a state he ceases to be a slave, because he continues to be a man and leaves behind him the law which made him a slave.

Originally a Whig, he changed his politics according to fluctuations in the antislavery movement. Elected as a Whig to the Cincinnati City Council in 1840, in 1841 he abandoned the Whigs, with which he had previously been affiliated, and for seven years was the undisputed leader of the United States Liberty Party in Ohio; he was remarkably skillful in drafting platforms and addresses, and it was he who prepared the national Liberty platform of 1843 and the Liberty address of 1845. Realizing in time that a third party movement could not succeed, he took the lead during the campaign of 1848 in combining the Liberty party with the Barnburners, or Van Buren Democrats of New York, to form the Free-Soilers.

In 1849 Chase was elected to the United States Senate from Ohio on the Free Soil Party, and in 1855 he was elected governor of Ohio. He drafted the famous Free-Soil platform, and it was largely through his influence that Van Buren was nominated for the presidency. His object, however, was not to establish a permanent new party organization, but to bring pressure to bear upon Northern Democrats to force them to adopt a policy opposed to the further extension of slavery.

During his service in the Senate (1849-1855) he was pre-eminently the champion of anti-slavery in that body, and no one spoke more ably than he did against the Compromise Measures of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Bill of 1854. The Kansas-Nebraska legislation, and the subsequent troubles in Kansas, having convinced him of the futility of trying to influence the Democrats, he assumed the leadership in the North-west of the movement to form a new party to oppose the extension of slavery. The Appeal of the Independent Democrats in Congress to the People of the United States, written by Chase and Giddings, and published in the New York Times of January 24, 1854, may be regarded as the earliest draft of the Republican party creed.

He was the first Republican governor of Ohio serving from 1855 to 1859.

He ran for the United States Republican Party nomination for the Presidency in 1860; at the Party convention he got 49 votes on the first ballot and afterwards threw his support to Abraham Lincoln. Although, with the exception of Seward, he was the most prominent Republican in the country, and had done more against slavery than any other Republican, he failed to secure the nomination for the presidency in 1860, partly because his views on the question of protection were not orthodox from a Republican point of view, and partly because the old line Whig element could not forgive his previous coalition with the Democrats.

Elected as a Republican to the United States Senate in 1860; took his seat March 4, 1861, but resigned two days later to become United States Secretary of the Treasury under Lincoln.

He was member of the Peace Convention of 1861 held in Washington, D.C., in an effort to devise means to prevent the impending war.

As secretary of the treasury in President Lincoln's cabinet from 1861 to 1864, during the first three years of the Civil War, he rendered services of the greatest value. That period of crisis witnessed two great changes in American financial policy, the establishment of a national banking system and the issue of a legal tender paper currency. The former was Chase's own particular measure. He suggested the idea, worked out all of the important principles and many of the details, and induced the Congress to accept them. The success of that system alone warrants his being placed in the first rank of American financiers. It not only secured an immediate market for government bonds, but it also provided a permanent uniform national currency, which, though inelastic, is absolutely stable. The issue of legal tenders, the greatest financial blunder of the war, was made contrary to his wishes, although he did not, as he perhaps ought to have done, push his opposition to the point of resigning.

The first U.S. federal currency was printed in 1862, during Chase's tenure as Secretary of the Treasury, thus it was his responsibility to design the notes. In an effort to further his political career, his own face appeared on a variety of U.S. paper currency. Most recently, in order to honor the man who introduced the modern system of banknotes, it was on the $10,000 bill, printed from 1928 to 1946. This bill is no longer in circulation.

Perhaps Chase's chief defect as a statesman was an insatiable desire for supreme office. It was partly this ambition, and also temperamental differences from the president, which led him to retire from the cabinet in June 1864. When Chase resigned as Treasury Secretary, Lincoln nominated Chase for the Supreme Court. Chase then served as Chief Justice of the United States to succeed Roger B. Taney, holding that position from 1864 until his death in 1873.

Temperamentally unsuited to judicial office, Chase nonetheless enhanced the prestige of the Supreme Court by his caution in dealing with Reconstruction measures and by his fairness in presiding over the Senate's impeachment trial (ending in acquittal) of President Andrew Johnson in 1868. In Mississippi v. Johnson (1867) and Georgia v. Stanton (1867), Chase spoke for the court in refusing to prohibit Johnson and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton from enforcing the Reconstruction Acts. By disavowing the court's jurisdiction in Ex parte McCardle (1868), Chase sidestepped the question of whether a U.S. military commission in a former Confederate state could try a civilian for opposing those statutes. He dissented when the court invalidated, in Cummings v. Missouri and Ex parte Garland (both 1867), state and federal loyalty oaths prerequisite to the practice of learned professions. In Texas v. White (1869) he asserted that the Constitution provided for an indestructible union. composed of indestructible states. In Veazie Bank v. Fenno (1869) he defended of that part of the banking legislation of the Civil War which imposed a tax of 10 percent on state banknotes. In Hepburn v. Griswold (1869), certain parts of the legal tender acts were declared to be unconstitutional. When the legal tender decision was reversed after the appointment of new judges, in 1871 and 1872, Chase prepared a very able dissenting opinion. In various cases in 1872-73 (near the end of his life), in a court whose majority narrowly construed the postwar Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution, he tried to protect the rights of blacks from infringement by state action.

Toward the end of his life he gradually drifted back toward his old Democratic position, and made an unsuccessful effort to secure the nomination of the Democratic party for the presidency in 1872. He also helped to found the Liberal Republican Party in 1872, and unsuccessfully sought its presidential nomination.

He died in New York City in 1873, and was interred in Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, D.C. and later reinterred in Spring Grove Cemetery, Cincinnati, Ohio.

The Chase Manhattan Bank was named for him, though he had no personal affiliation with it.

Chase's daughter, Kate, was a notable socialite in her own right as the Civil War "Belle of Washington", acting as her father's official hostess and unofficial campaign manager. Her November 12, 1863 marriage to the textile magnate Rhode Island politician William Sprague did not flourish. After her father's death the marriage detoriated further with Sprague's marital infidelities, alcoholism, and constant belittling of Chase's spending habits, where Chase in turn had an affair with Roscoe Conkling. They divorced in 1882, and Chase later died in poverty in 1899.

Chase was born in Cornish, New Hampshire, and lost his father when he was nine years old. He was raised and educated by his uncle, Bishop Philander Chase, the first Episcopal bishop of Ohio and later of Illinois. He studied in the common schools of Windsor, Vermont, Worthington, Ohio, and at the Cincinnati College, and graduated from Dartmouth College in 1826. He studied under U.S. Attorney General William Wirt (1827-30) and was admitted to the bar

Chase was born in Cornish, New Hampshire, and lost his father when he was nine years old. He was raised and educated by his uncle, Bishop Philander Chase, the first Episcopal bishop of Ohio and later of Illinois. He studied in the common schools of Windsor, Vermont, Worthington, Ohio, and at the Cincinnati College, and graduated from Dartmouth College in 1826. He studied under U.S. Attorney General William Wirt (1827-30) and was admitted to the bar