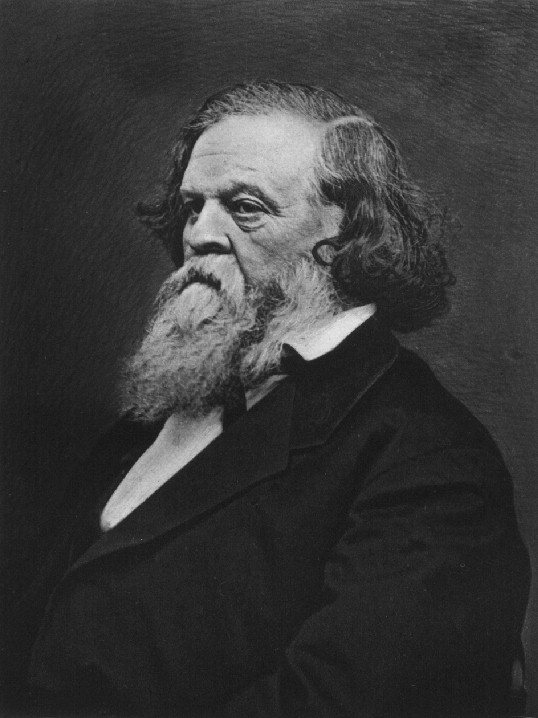

Howell Cobb (1815-1868)

A mid-nineteenth-century politician, Howell Cobb served as congressman (1843-51 and 1855-57), Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives (1849-51), governor of Georgia (1851-53), and secretary of the treasury (1857-60). Following Georgia's secession from the Union in 1861, he served as president of the Confederate Provisional Congress (1861-62) and a major general of the Confederate army.

Cobb was born in Jefferson County on September 7, 1815, the eldest child of John and Sarah Cobb. His younger brother, Thomas R. R. Cobb, became a prominent jurist and Confederate general. Around 1819 the family moved to Athens, where Cobb attended the University of Georgia, graduating in 1834. He became an attorney in 1836. His marriage in 1835 to Mary Ann Lamar produced twelve children, six of whom survived to adulthood.

Cobb was born in Jefferson County on September 7, 1815, the eldest child of John and Sarah Cobb. His younger brother, Thomas R. R. Cobb, became a prominent jurist and Confederate general. Around 1819 the family moved to Athens, where Cobb attended the University of Georgia, graduating in 1834. He became an attorney in 1836. His marriage in 1835 to Mary Ann Lamar produced twelve children, six of whom survived to adulthood.

Political Career

Although the practice of law provided Cobb with a profession, politics was his avocation. Like his father, he embraced the doctrines of the Jacksonian Democrats, which he defended first in university debating societies and then on the stump. In 1837 the state legislature elected him solicitor general for the Western Judicial Circuit of Georgia. In 1842 Georgia Democrats nominated him to Congress representing the Sixth District, an election he won easily.

Cobb's affability and quick mastery of House rules hastened his advancement within the Democratic caucus. Already, sectional disputes touching on slavery and its future tainted congressional debates. From both inclination and political necessity, the young congressman labored to protect southern interests in these struggles. He believed that the best security for slavery and the South lay within a federal union of equal partners based upon adherence to the Constitution. Unlike "fire-eating" southerners, however, he believed that this goal could be achieved only through a pro-Union policy of compromise in times of sectional controversy. Consequently, Cobb engaged extreme southern states' rights men with the same vigor that he directed toward northern abolitionists. As a result of these battles, he later found his path to higher office blocked by opponents within the Georgia Democratic Party.

During the late 1840s the dispute over slavery reached crisis proportions as Congress attempted to resolve the future of slavery in western territories acquired as a result of the Mexican-American War (1846-48). Elected Speaker of the Thirty-first Congress, Cobb labored both behind the scenes and in his rulings from the chair to assist in securing passage of the Compromise of 1850. The following year he was elected governor at the head of a pro-compromise coalition of Union Democrats and Whigs. The success of this Constitutional Union Party helped solidify the South's acceptance of the Compromise of 1850, but it earned Cobb the permanent enmity of many southern-rights Democrats and damaged his standing with the national Democratic Party. He found himself politically isolated after the Constitutional Union organization collapsed in 1852 when its Whig wing, led by Alexander H. Stephens and Robert Toombs, declined to join the national Democracy.

At the conclusion of his gubernatorial term in 1853, Cobb returned to private life but worked diligently to restore his standing within the Democratic Party. He reacted gracefully in 1853 when southern-rights Democrats in the state legislature blocked his election to the Senate, and in 1855 he regained his congressional seat. In the presidential election of 1856 Cobb campaigned vigorously on behalf of Democratic nominee James Buchanan, who then rewarded his efforts by naming him treasury secretary.

During Cobb's tenure at the Treasury Department, the financial panic of 1857 beset the nation. Yet the ongoing crisis over slavery in the territories remained a more serious threat to the nation's future than any temporary economic dislocation. Throughout his political life Cobb had argued that only the national Democratic Party could effect the compromises essential to the maintenance of the Union. By 1860 the sectional pressures over slavery had grown so intense that the Democratic Party split into northern and southern organizations. This split, combined with the rise of the Republican Party in the North, served to place control of the federal government in the hands of an antislavery party. Confronted with the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency, Cobb abandoned his faith in the Union and forcefully urged Georgia's secession.

Civil War and Reconstruction

Following secession, Cobb served as president of the Confederate Provisional Congress.

He received some consideration for the Confederate presidency, but lingering animosities among southern-rights men effectively denied him the post. At the conclusion of his term he entered the Confederate army. He began his service as colonel of the Sixteenth Georgia Infantry and eventually rose to the rank of major general. He saw service in Virginia during the Peninsula campaign and the Seven Days Battles. In October 1862 he was transferred to the district of middle Florida, and then in September 1863 he took command of Georgia state troops. He surrendered his troops to Union forces in Macon, Georgia, on April 20, 1865.

Cobb declined to make any public remarks on Reconstruction policy pending receipt of a presidential pardon. That pardon came three years after the war's end. He promptly delivered a series of speeches in the summer of 1868, bitterly denouncing Radical Republican plans for Reconstruction.

He died of a heart attack while vacationing in New York on October 9, 1868.

From The New Georgia Encyclopedia.

Cobb was born in Jefferson County on September 7, 1815, the eldest child of John and Sarah Cobb. His younger brother, Thomas R. R. Cobb, became a prominent jurist and Confederate general. Around 1819 the family moved to Athens, where Cobb attended the University of Georgia, graduating in 1834. He became an attorney in 1836. His marriage in 1835 to Mary Ann Lamar produced twelve children, six of whom survived to adulthood.

Cobb was born in Jefferson County on September 7, 1815, the eldest child of John and Sarah Cobb. His younger brother, Thomas R. R. Cobb, became a prominent jurist and Confederate general. Around 1819 the family moved to Athens, where Cobb attended the University of Georgia, graduating in 1834. He became an attorney in 1836. His marriage in 1835 to Mary Ann Lamar produced twelve children, six of whom survived to adulthood.