Civil War

Civil War

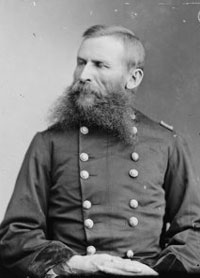

George Crook (1828-1890)

George Crook (September 8, 1828 - March 21, 1890) was a career U.S. Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars.

Early Life

Crook was born to Thomas and Elizabeth Matthews Crook on a farm near Taylorsville, Ohio (near Dayton). He graduated from West Point in 1852, ranking near the bottom of his class. His first assignment was with the 4th Infantry, serving in Oregon and northern California and fighting against several Native American tribes.

He married a Virginian, Mary Tapscott Dailey.

Civil War

Civil War

When the U.S. Civil War broke out, Crook accepted a commission as Colonel of Ohio's 36th regiment and led it on duty in western Virginia. He was promoted to the rank of brigadier general in August 1862. He commanded a brigade of Ohio regiments in the Kanawah Division (attached to the IX Corps, Army of the Potomac) in the Maryland Campaign. Crook saw action at the battles of South Mountain and Antietam. He developed a life-long friendship with one of his subordinates, Col. Rutherford B. Hayes of the 23rd Ohio Infantry.

General Crook commanded a cavalry division in the Army of the Cumberland at the battle of Chickamauga, and then returned to the eastern front as chief of the Kanawah Division.

Southwest Virginia

To open the spring campaign of 1864, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant ordered a Union advance on all fronts, minor as well as major. Grant sent for Brigadier General Crook, in winter quarters at Charleston, West Virginia, and ordered him to attack the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, Richmond's primary link to Knoxville and the southwest, and to destroy the Confederate salt works at Saltville, Virginia.

The 35-year-old Crook, the most magnificently whiskered Civil War general on either side, reported to army headquarters at City Point, Virginia, where the commanding general explained the mission in person. Grant instructed Crook to march his force, the Kanawha Division, against the railroad at Dublin, Virginia, 140 miles south of Charleston. At Dublin he would put the railroad out of business and destroy Confederate military property. He was then to destroy the railroad bridge over New River, a few miles to the east. When these actions were accomplished, along with the destruction of the salt works, Crook was to march east and join forces with Major General Franz Sigel, who meanwhile was to be driving south up the Shenandoah Valley.

Crook returned to Charleston and set his force in motion. After long dreary months of garrison duty, the men were ready for action. Crook did not reveal the nature or objective of their mission, but everyone sensed that something important was brewing. "All things point to early action," the commander of the second brigade, Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes, noted in his diary.

On April 29, 1864, the Kanawha Division marched out of Charleston and headed south. Crook sent a force under Brigadier General William W. Averell westward towards Saltville, then pushed on towards Dublin with nine infantry regiments, seven cavalry regiments, and 15 artillery pieces, a force of about 6,500 men organized into three brigades. The West Virginia countryside was beautiful that spring, but the mountainous terrain made the march a difficult undertaking. The way was narrow and steep, and spring rains slowed the march as tramping feet churned the roads into mud. In places, Crook's engineers had to build bridges across wash-outs before the army could advance.

The column reached Fayette on May 2, and then passed through Raleigh Court House and Princeton. On the night of May 8, the division camped at Shannon's Bridge, Virginia, 10 miles north of Dublin.

The Confederates at Dublin soon learned the enemy was approaching. Their commander, Colonel John McCausland, prepared to evacuate his 1100 men, but before transportation could arrive, a courier from Brigadier General Albert G. Jenkins informed McCausland that the two of them were ordered by General John C. Breckenridge to stop Crook's advance. The combined forces of Jenkins and McCausland amounted to 2,400 men. Jenkins, the senior officer, took command.

Breaking camp on the morning of May 9, Crook moved his men south to the top of a spur of Cloyd's Mountain. Before the Union troops lay a precipitous, densely wooded slope with a meadow about 400 yards wide at the bottom. On the other side of the meadow, the land rose in another spur of the mountain, and there Jenkins' rebels waited behind hastily erected fortifications.

Crook dispatched the third brigade under Colonel Carr B. White to work its way through the woods and deliver a flank attack on the rebel right. At 11 am, he sent Hayes' first brigade and Colonel Horatio G. Sickel's second brigade down the slope to the edge of the meadow, where they were to launch a frontal assault on the Confederates as soon as they heard the sound of White's guns.

The slope before them was so steep that the officers had to dismount and descend on foot. Crook stationed himself with Hayes' brigade, which was to lead the assault. After a long, anxious wait, Hayes at last heard cannon fire off to his left and led his men at a slow double time out onto the meadow and into the rebels' musketry and artillery fire, which Crook called "galling". Their pace quickened as they neared the other side, but just before the up-slope they came to a waist-deep creek. The barrier caused little delay and the Yankee infantry stormed up the hill and engaged the rebel defenders at close range.

The only man to have trouble with the creek was General Crook. Dismounted, he still wore his high riding boots, and as he stepped into the stream, the boots filled with water and bogged him down. Nearby soldiers grabbed their commander's arms and hauled him to the other side.

Vicious hand-to-hand fighting erupted as the Yankees reached the crude rebel defenses. The Southerners gave way, tried to re-form, then broke and retreated up and over the hill towards Dublin.

The Yankees rounded up rebel prisoners by the hundreds and seized General Jenkins, who had fallen wounded. At this point the discipline of the Union men wavered, and there was no organized pursuit of the fleeing enemy. General Crook was unable to provide leadership as the excitement and exertion had sent him into a faint.

Colonel Hayes kept his head and organized a force of about 500 men from the soldiers milling about the site of their victory. With his improvised command, he set off, closely pressing the rebels.

While the fight at Cloyd's Mountain was going on, a train pulled into the Dublin station and disgorged 500 fresh troops of General John Hunt Morgan's cavalry, which had just defeated Averell at Saltville. The fresh troops hastened towards the battlefield, where they soon met their compatriots retreating from Cloyd's Mountain. The reinforcements halted the rout, but Colonel Hayes, although ignorant of the strength of the force now before him, immediately ordered his men to "yell like devils" and rush the enemy. Within a few minutes General Crook arrived with the rest of the division, and the defenders broke and ran.

Cloyd's Mountain cost the Union army 688 casualties, while the rebels suffered 538 killed, wounded, and captured.

Unopposed, Crook moved his command into Dublin, where he laid waste to the railroad and the military stores. He then sent a party eastward to tear up the tracks and burn the ties. The next morning the main body set out for their next objective, the New River bridge, a key point on the railroad, a few miles to the east.

The Confederates, now commanded by Colonel McCausland, waited on the east side of the New River to defend the bridge. Crook pulled up on the west bank, and a long, ineffective artillery duel ensued. Seeing that there was little danger from the rebel cannon, Crook ordered the bridge destroyed, and both sides watched in awe as the structure collapsed magnificently into the river. McCausland, without the resources to oppose the Yankees any further, withdrew his battered command to the east.

General Crook, supplies running low in a country not suited for major foraging, now entertained second thoughts about his orders to push on east and join Sigel in the Shenandoah Valley. At Dublin he had intercepted an unconfirmed report that General Robert E. Lee had beaten Grant badly in the Wilderness, which led him to consider whether the Confederate commander might not soon move against Crook with a vastly superior force.

Having accomplished the major part of his mission, destruction of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, Crook turned his men north and after another hard march, reached the Union base at Meadow Bluff, West Virginia.

Shenandoah Valley

The following August, Crook took command of the Department and Army of Western Virginia, the forces of which became the VIII Corps in Major General Philip Sheridan's Army of the Shenandoah. Crook led his corps in the Valley Campaigns of 1864 at the battles of Opequon (Third Winchester), Fisher's Hill, and Cedar Creek. In October he was promoted to major general of volunteers.

In February, 1865, General Crook was captured by Confederate raiders at Cumberland, Maryland, and held as a prisoner of war in Richmond until exchanged a month later, when he took command of a cavalry division in the Army of the Potomac during the Appomattox Campaign.

Indian Wars

At the end of the Civil War, George Crook received a brevet as Major General in the regular army, but reverted to the permanent rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, serving with the 23rd Infantry on frontier duty in the Pacific Northwest. He campaigned against the Paiute Indians where he won the recognition of President Ulysses S. Grant. Grant placed Crook in command of the Arizona. Crook's use of Apache scouts brought him much success in forcing the Apache Indians, under chief Cochise onto resrvations. In 1872 the Arizona Territory was at peace and Crook was appointed brigadier general in the regular army, a promotion that passed over and angered several full colonels next in line for promotion to general. He next served against the Sioux in the 1876 Powder River Expedition. He fought the Lakota at the Battle of the Rosebud, as well as at the Tongue River.

By 1882, Crook was back in command in Arizona. The Apaches had once again taken up arms against the U.S. army under the leadership of Geronimo. Crook repeatedly forced the surrender of the Apaches but saw Geronimo escape. Nelson A. Miles replaced Crook in command of the Arizona Territory and brought an end to the Apache Wars when he sent Geronimo, the Apache nation and the Apache scouts serving in the U.S. army into exile in Florida. After years of campaigning in the Indian Wars, Crook won steady promotion back up the ranks to the permanent grade of Major General, and President Grover Cleveland placed him in command of the Department of the West in 1888.

He spent his last years speaking out against the unjust treatment of his former Indian adversaries. He suddenly died in Chicago while serving as commander of the Division of the Missouri. Crook was originally buried in Oakland, Maryland, but was moved to Section 2 of Arlington National Cemetery on November 11, 1898.

The Indian chief, Red Cloud said of Crook when he died, "he never lied to us. His words gave us hope".

In memoriam

Crook County, Wyoming, is named in George Crook's honor, as is "Crook Walk" in the Arlington National Cemetery.