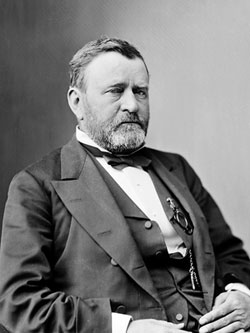

Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885)

Ulysses S. Grant (April 27, 1822 - July 23, 1885) was a Union general in the American Civil War and the 18th President of the United States (1869-1877).

Grant won many important battles, rose to become general-in-chief of all Union armies, and is credited with winning the war. Although he was a successful general, he is considered by historians to be one of America's worst presidents, who led an administration plagued by severe scandal and corruption.

Historians agree that Grant was not personally corrupt; it was his subordinates in the executive branch who were at fault. He is instead mostly criticized for not taking a strong stance against the corruption, and not acting to stop it. More recent treatments have emphasized the accomplishments of his administration, including his struggle to preserve Reconstruction, and looked with more understanding upon its shortcomings.

Early Life

Grant was born Hiram Ulysses Grant in Point Pleasant, Clermont County, Ohio, 25 miles (40 km) north of Cincinnati on the Ohio River, to Jesse Grant and Hannah Simpson. His father, a tanner, and his mother were born in Pennsylvania. In the fall of 1823 they moved to the village of Georgetown in Brown County, Ohio, where Grant spent most of his time until he was 17.

At the age of 17, Grant received a cadetship to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, through his U.S. Congressman, Thomas L. Hamer. Hamer erroneously nominated him as Ulysses Simpson Grant, and although Grant protested the change, it was difficult to resist the bureaucracy. Upon graduation, Grant adopted the form of his new name with middle initial only, never acknowledging that the "S" stood for Simpson. He graduated from West Point in 1843, ranking 21st in a class of 39. At the academy, he established a reputation as a fearless and expert horseman.

Grant married Julia Boggs Dent (1826-1902) on August 22, 1848. They had four children: Frederick Dent Grant, Ulysses S. (Buck) Grant, Jr., Ellen (Nellie) Grant, and Jesse Root Grant.

Military career

Grant served in the Mexican-American War under Generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott, taking part in the battles of Resaca de la Palma, Palo Alto, Monterrey, and Veracruz. He was twice brevetted for bravery: at Molino del Rey and Chapultepec. On July 31, 1854, he resigned from the army. Seven years of civilian life followed, in which he was a farmer, a real estate agent in St. Louis, and finally an assistant in the leather shop owned by his father and brother.

On April 24, 1861, ten days after the fall of Fort Sumter, Captain Grant arrived in Springfield, Illinois, with a company of men he had raised. The governor felt that a West Point man could be put to better use and appointed him colonel of the 21st Illinois Infantry (effective June 17, 1861). On August 7, Grant was appointed a brigadier general of volunteers.

Grant gave the Union Army its first major victory of the American Civil War by capturing Fort Henry, Tennessee, on February 6, 1862, followed by Fort Donelson, where he demanded the famous terms of "unconditional surrender" and captured a Confederate army. Later in 1862, he was surprised by Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston at the Battle of Shiloh, but with grim determination and timely reinforcements, Grant turned a serious reverse into a victory in the second day of battle. His strategy in the campaign to capture the river fortress of Vicksburg, Mississippi, in 1863 is considered one of the most masterful in military history; it split the Confederacy in two, and it represented the second major Confederate army to surrender to Grant.

Grant was the savior of Union forces besieged in Chattanooga, Tennessee, decisively beating Braxton Bragg and opening an avenue to Atlanta, Georgia, and the heart of the Confederacy. His willingness to fight and ability to win impressed President Abraham Lincoln, who appointed him lieutenant general—a new rank recently authorized by the U.S. Congress with Grant in mind—on March 2, 1864. On March 12, Grant became general-in-chief of all of the armies of the United States.

Grant's fighting style was what one fellow general called "that of a bulldog". Although a master of combat by out-maneuvering his opponent (such as at Vicksburg and in the Overland Campaign against Robert E. Lee), Grant was not afraid to order direct assaults or tight sieges against Confederate forces, often when the Confederates were themselves launching offensives against him. Once an offensive or a siege began, Grant refused to stop the attack until the enemy surrendered or was driven from the field. Such tactics often resulted in heavy casualties for Grant's men, but they wore down the Confederate forces proportionately even more and inflicted irreplaceable losses. Grant has been described as a "butcher" for his strategy, particularly in 1864, but he was able to achieve objectives that his predecessor generals had not, even though they suffered similar casualties over time.

In March 1864, Grant put Major General William T. Sherman in immediate command of all forces in the West and moved his headquarters to Virginia where he turned his attention to the long-frustrated Union effort to destroy the army of Robert E. Lee; his secondary objective was to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, but Grant knew that the latter would happen automatically once the former was accomplished. He devised a coordinated strategy that would strike at the heart of Confederacy from multiple directions: Grant, George G. Meade, and Benjamin Franklin Butler against Lee near Richmond; Franz Sigel in the Shenandoah Valley; Sherman to invade Georgia, defeat Joseph E. Johnston, and capture Atlanta; George Crook and William W. Averell to operate against railroad supply lines in West Virginia; Nathaniel Banks to capture Mobile, Alabama. Grant was the first general to attempt such a coordinated strategy in the war and the first to understand the concepts of total war, in which the destruction of an enemy's economic infrastructure that supplied its armies was as important as tactical victories on the battlefield.

The Overland Campaign pitted Grant against Lee, starting in May 1864. Despite heavy losses, the Army of the Potomac kept up a relentless pursuit of Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Grant battled Lee to a draw in the Battle of the Wilderness, had no more than a draw at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, and lost with horrible casualties at the Battle of Cold Harbor. Unfortunately for Grant's coordinated strategy, only Sherman's advance into Georgia was making progress. All of the other generals were imposed upon Grant for political reasons, and they bogged down without much success.

Despite the heavy losses, Grant did not retreat as his predecessors had done following their setbacks. Finally, he slipped his troops across the James River, fooling Lee. Failing to capture the rail junctions at Petersburg, Virginia, Grant settled in to a nine-month siege of Lee's army in the city. He dispatched Philip Sheridan to the Shenandoah Valley to defeat the army of Jubal A. Early and destroy the farms supplying Lee. Grant's relentless pressure finally forced Lee to evacuate Richmond and surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. Grant offered generous terms that did much to ease the tensions between the armies and preserve some semblance of Southern pride, which would be needed to reconcile the warring sides. Within a few weeks, the American Civil War was effectively over, although minor actions would continue until Kirby Smith surrendered his forces in the Trans-Mississippi Department on June 2, 1865.

Immediately after Lee's surrender, Grant had the sad honor of serving as a pallbearer at the funeral of his greatest champion, Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln had been quoted after the massive losses at Shiloh, "I can't spare this general. He fights." It was a two-word description that completely caught the essence of Ulysses S. Grant.

After the war, the Congress authorized Grant the newly created rank of General of the Army (the equivalent of a four-star, "full" general rank in the modern Army). He was appointed as such by President Andrew Johnson on July 25, 1866.

Presidency

Grant was the 18th President of the United States and served two terms from March 4, 1869, to March 3, 1877. He was chosen as the Republican presidential candidate at the Republican National Convention in Chicago on May 20, 1868, with no real opposition. In the general election that year, he won with a majority of 3,012,833 out of a total of 5,716,082 votes cast.

Grant's presidency was plagued with scandals, such as the Sanborn Incident at the Treasury and problems with U.S. Attorney Cyrus I. Scofield. The most famous scandal was the Whiskey Ring fraud in which over $3 million in taxes were taken from the federal government. Orville E. Babcock, the private secretary to the President, was indicted as a member of the ring and escaped conviction only because of a presidential pardon. After the Whiskey Ring, Grant's Secretary of War, William W. Belknap, was involved in an investigation that revealed that he had taken bribes in exchange for the sale of Native American trading posts.

Although there is no evidence that Grant himself profited from corruption among his subordinates, he did not take a firm stance against malefactors and failed to react strongly even after their guilt was established. He was weak in his selection of subordinates. He alienated party leaders by giving many posts to his friends and political contributors, rather than listen to their recommendations. His failure to establish adequate political allies was a factor in the scandals getting out of control.

Grant was known to visit the Willard Hotel to escape the stress of the White House. He referred to the people who approached him in the lobby as "those damn lobbyists," possibly giving rise to the modern term lobbyist.

Despite all the scandals, Grant's administration presided over significant events in U.S. history. The most tumultuous was the continuing process of Reconstruction. He favored a limited number of troops to be stationed in the south—sufficient numbers to protect rights of southern blacks and suppress the violent tactics of the Ku Klux Klan; not so many that would harbor resentment in the general population. In 1869 and 1871, Grant signed bills promoting voting rights and prosecuting Klan leaders. The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, establishing voting rights, was ratified in (1870).

Also during the Grant administration, the U.S. Department of Justice (1870), the Post Office Department (1872), and the Office of the U.S. Solicitor General (1870) were instituted and organized. In 1871, the "Advisory Board on Civil Service" was instituted; after it expired in 1873, it became the role model for the "Civil Service Commission" instituted in 1883 by President Chester A. Arthur, a Grant faithful. (Today it is known as the Office of Personnel Management.) In 1876, Colorado was admitted into the union. In foreign affairs the greatest achievement of the Grant administration was the "Treaty of Washington" negotiated by Grantīs best appointment, Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, in 1871. In 1876 he helped to calm the nation over the Hayes-Tilden election controversy by appointing a federal commission that helped to settle the election.

Supreme Court appointments

Grant appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States: William Strong (1870), Joseph P. Bradley (1870), Ward Hunt (1873), Morrison Remick Waite (Chief Justice - 1874).

States Admitted to the Union:

Colorado - August 1, 1876

Later life

After the end of his second term, Grant spent two years traveling around the world. He visited Sunderland, where he opened the first free municipal public library in England. Grant also visited Japan. In the Shibakoen section of Tokyo, a tree still stands that Grant planted during his stay.

In 1879, the Meiji government of Japan announced the annexation of the Ryukyu Islands. China objected, and Ulysses S. Grant was asked to arbitrate the matter. He decided that Japan's claim to the islands was stronger and ruled in Japan's favor.

In 1883, Grant was elected the eighth president of the National Rifle Association.

In 1881, Grant placed almost all of his financial assets into an investment banking partnership with Ferdinand Ward, as suggested by Grant's son Buck (Ulysses, Jr.), who was having success of Wall Street. Ward was known as the "Young Napoleon of Finance." Perhaps Grant should have taken that name seriously; as with the other Young Napoleon, George B. McClellan, failure was in the wings. In this case, Ward swindled Grant in 1884, bankrupted the company, Grant and Ward, and fled. Grant and his family were left destitute (this was before the era in which retired U.S. Presidents were given pensions).

The author Mark Twain had admired some magazine articles Grant had written about the war and offered to publish Grant's memoirs. Grant was terminally ill from throat cancer and fought to finish his memoirs in the hope they would provide financially for his family after his death. Although wracked with pain and almost unable to speak at the end, he finished them just a few days before his death. The memoirs succeeded in providing a comfortable income for his wife and children, selling over 300,000 copies and earning the Grant family over $450,000 ($9,500,000 in 2005 dollars). Clemens called the memoirs "the most remarkable work of its kind since the Commentaries of Julius Caesar," and they are widely regarded as among the finest memoirs ever written.

Ulysses S. Grant died on July 23, 1885, at Mount McGregor, Saratoga County, New York. His body lies in New York City, beside that of his wife, in Grant's Tomb, the largest mausoleum in North America.

(From the Wikipedia Encyclopedia).