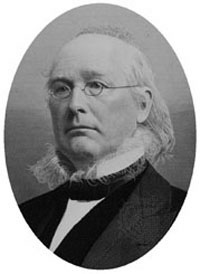

Horace Greeley (1811-1872)

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 - November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and politician, known especially for his articulation of the North's vigorous antislavery sentiments during the 1850s.

A printer's apprentice in East Poultney, Vermont., he moved to New York City, where he became senior editor for a new literary magazine, The New Yorker (1834). A liberal Whig, Greeley caught the attention of New York political boss Thurlow Weed and was asked to issue political campaign weeklies in the elections of 1838 and 1840. These publications substantially aided the Whig cause and marked the beginning of Greeley's political partnership with Weed and New York governor William H. Seward (secretary of state, 186169), which lasted till 1854.

His journalistic success encouraged him to embark on a more ambitious newspaper venture. The New York Tribune, which he founded in 1841 and edited until his death, became a daily Whig paper dedicated to a medley of reforms, economic progress, and the elevation of the masses. The Tribune set a particularly high standard in its news-gathering, intellectual interest, and moral fervour. Greeley, who produced a prodigious amount of high-quality editorial copy, came to be considered the outstanding newspaper editor of his time; his large and competent staff cooperated to make the paper a "political Bible" for many readers throughout the North. His passion for detail distinguished modern newspapers' fact-supported and statistic orientation from the more discursive editorial essays then current in newspaper writing.

Reflecting his highly moral New England upbringing, he was an unrelenting foe of liquor, tobacco, gambling, prostitution, and capital punishment. He urged a variety of educational reforms, especially free common-school education for all; he championed producers' cooperatives but opposed women's suffrage.

In the early 1850s, Greeley became increasingly bitter over the failure of his Whig colleagues to support him for high public office—a lifelong ambition. He also grew disenchanted with the party's ambivalence toward slavery, which he opposed on both moral and economic grounds. In 1854 he transferred his allegiance to the newly emerging Republican Party, which he helped organize. Throughout the decade, Greeley's newspaper constantly fed the rising antislavery excitement of the North; his paper became anathema to slaveholders of the South. His editorial columns consistently opposed compromising the slavery issue, as he argued against popular sovereignty (local option) in the territories, urged unrestricted free speech and mail privileges for Abolitionists, encouraged Free-Soilers, who would oppose slavery in the Kansas Territory, and advocated forcible resistance to federal fugitive-slave hunters.

After the onset of the Civil War (1861), Greeley pursued an erratic course, though generally he sided with the Radical Republicans in advocating early emancipation of the slaves and, later, civil rights for freedmen. He lost much public respect by opposing the renomination of President Abraham Lincoln in 1864 and in signing the bail bond of former Confederate president Jefferson Davis in 1867.

Greeley was an agrarian and supported liberal policies towards settlers: one of his famous phrases was "Go West, young man".

Partly out of political pique and partly from disagreement with the corruption apparent in the first administration of President Ulysses S. Grant (1869-73), he joined a group of Republican dissenters, forming the Liberal Republican Party, which opposed Grant in 1872. The party nominated Greeley for president, and, in the dreary campaign that followed, Greeley was so mercilessly attacked that, as he said, he scarcely knew whether he was running for the presidency or the penitentiary. Despite the faction's inexperience, Greeley polled more than 40 percent of the popular vote; he died before the electoral college met, and his 86 electoral votes went to four minor candidates.

While Greeley had been pursuing his political career, Whitelaw Reid, owner of the New York Herald had gained control of the Tribune. Weeks later, Greeley, in his final illness, spotting Reid, cried out "You son of a bitch, you stole my newspaper", and died. Reid reported Greeley's last words as "I know my redeemer liveth".

Greeley had a long, but unhappy, marriage to Mary Cheney Greeley, a sometime Suffragette. Mary Cheney Greeley believed in spirits and was a rigorous adherent of The Graham Diet. Mrs. Greeley doted on one son to the extent that an infant daughter died from neglect. The eventual death of that son was devastating to Mrs. Greeley. Horace Greeley spent as little time as possible with his wife and would sleep in a boarding house when in New York City. After the death of the Greeley couple the two daughters found thousands of dollars worth of china, objets d'art, and finery under covers in the basement.