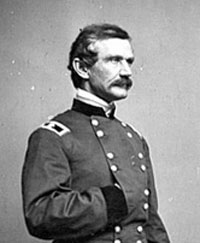

Andrew Atkinson Humphreys (1810-1883)

Andrew Atkinson Humphreys (November 2, 1810 - December 27, 1883), was a career U.S. Army officer, civil engineer, and a Union general in the American Civil War. He served in senior positions in the Army of the Potomac, including division command, chief of staff, and corps command, and was Chief Engineer of the U.S. Army.

Humphreys was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to a family prominent in naval architecture; his grandfather, Joshua, designed "Old Ironsides", the USS Constitution. Andrew graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in 1831 and spent much of the next thirty years as a civil engineer in the Army. He saw combat in the artillery in the Seminole Wars. Much of his service involved topographical and hydrological surveys of the Mississippi River Delta.

Humphreys was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to a family prominent in naval architecture; his grandfather, Joshua, designed "Old Ironsides", the USS Constitution. Andrew graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in 1831 and spent much of the next thirty years as a civil engineer in the Army. He saw combat in the artillery in the Seminole Wars. Much of his service involved topographical and hydrological surveys of the Mississippi River Delta.

After the outbreak of the Civil War, Humphreys was promoted (August 6, 1861) to major and became chief topographical engineer in Major General George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac. Initially involved in planning the defenses of Washington, D.C., by March, 1862, he shipped out with McClellan for the Peninsula Campaign.

He was promoted to brigadier general of volunteers April 28 and on September 12 assumed command of the new 3rd Division in the V Corps of the Army of the Potomac. He led the division in a reserve role in the Battle of Antietam.

At the Battle of Fredericksburg, his division achieved the farthest advance against fierce Confederate fire from Marye's Heights; his corps commander, George G. Meade, wrote: "He behaved with distinguished gallantry at Fredericksburg." For an officer with little combat experience, he inspired his troops with his personal bravery, as he later wrote:

" ... for certain good reasons connected with the effect of what I did upon the spirit of the men and from an invincible repugnance to ride anywhere else, I always rode at the head of my troops." Lt. Cavada of the general's staff recalled that just before he took his troops up to the Stone Wall at Fredericksburg, Humphreys had bowed to his staff in his courtly way, "and in the blandest manner remarked, 'Young gentlemen, I intend to lead this assault; I presume, of course, you will wish to ride with me?'" Since it was put like that, the staff had done so, and five of the seven officers were knocked off their horses. After his men had taken as much as they could stand in front of the Stone Wall on Marye's Heights, the next brigade coming up the hill saw Humphreys sitting his horse all alone, looking out across the plain, bullets cutting the air all around him. Something about the way the general was taking it pleased them, and they sent up a cheer. Humphreys looked over, surprised, waved his cap to them with a grim smile, and then went riding off into the twilight. In this way Humphreys had turned his first division's dislike of him into admiration for his heroic leadership ..."

Although respected by his men for his bravery under fire, Humphreys was not well liked by them. In his mid-fifties, they considered him an old man, despite his relatively youthful appearance. His nickname was "Old Goggle Eyes" for his eyeglasses. He was a taskmaster and strict disciplinarian. Charles A. Dana, the Assistant Secretary of War, called him a man of "distinguished and brilliant profanity."

At the Battle of Chancellorsville, Humphreys' division did little, principally because most of his soldiers were near the ends of their enlistments.

On May 23, 1863, Humphreys was transferred to the command of the 2nd Division in the III Corps, under Major General Daniel E. Sickles. When Meade assumed command of the Army of the Potomac just before the Battle of Gettysburg, he asked Humphreys to be his chief of staff, replacing Daniel Butterfield, who was considered to be too close politically to the previous commander, Joseph Hooker. Humphreys declined the opportunity to give up his division command.

His new division immediately saw action at Gettysburg where, on July 2, 1863, Sickles insubordinately moved his corps from its assigned defensive position on Cemetery Ridge. Humphrey's new position was on the Emmitsburg Road, part of a salient directly in the path of the Confederate assault, and it was too long a front for a single division to defend. Assaulted by the division of Lafayette McLaws, Humphrey's two brigades were demolished; Sickles had pulled back Humphrey's reserve brigade to shore up the neighboring division (David B. Birney), which was the first to be attacked. Humphreys put up the best fight that could have been expected and was eventually able to reform his survivors on Cemetery Ridge, but his division and the entire corps were finished as a fighting force.

Humphreys was promoted to major general of volunteers on July 8, 1863, and finally acceded to Meade's request to serve as his chief of staff; he did not have much of division left to command. He served in that position through the Bristoe and Mine Run campaigns that fall, and the Overland Campaign and the Siege of Petersburg in 1864.

In November, 1864, he assumed command of the II Corps, which he led for the rest of the siege and during the pursuit of Robert E. Lee to Appomattox Court House and surrender. On March 13, 1865, he was brevetted brigadier general in the Regular Army for "gallant and meritorious service at the battle of Gettysburg", and then to major general for the Battle of Sayler's Creek during Lee's retreat.

After the war, Humphreys commanded the District of Pennsylvania. He became a permanent brigadier general and Chief of Engineers in 1866, a position he held until June 30, 1879, when he retired, serving during this period on lighthouse and other engineering boards.

In retirement, Humphreys studied philosophy. He was one of the incorporators of the National Academy of Sciences. Humphreys' published works were highlighted by his 1867 Report on the Physics and Hydraulics of the Mississippi River, which gave him considerable prominence in the scientific community. He also wrote personal accounts of the war, published in 1883: From Gettysburg to the Rapidan and The Virginia Campaign of '64 and '65.

He died in Washington, D.C., in 1883 and is buried there in the Congressional Cemetery.

Humphreys was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to a family prominent in naval architecture; his grandfather, Joshua, designed "Old Ironsides", the USS Constitution. Andrew graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in 1831 and spent much of the next thirty years as a civil engineer in the Army. He saw combat in the artillery in the Seminole Wars. Much of his service involved topographical and hydrological surveys of the Mississippi River Delta.

Humphreys was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to a family prominent in naval architecture; his grandfather, Joshua, designed "Old Ironsides", the USS Constitution. Andrew graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in 1831 and spent much of the next thirty years as a civil engineer in the Army. He saw combat in the artillery in the Seminole Wars. Much of his service involved topographical and hydrological surveys of the Mississippi River Delta.