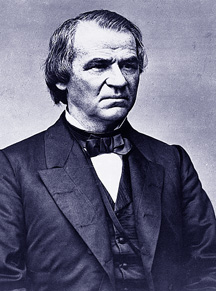

Andrew Johnson (1808-1875)

Andrew Johnson was born in a log cabin to nearly illiterate parents on December 29, 1808, in Raleigh, North Carolina. His father, Jacob Johnson, had scratched out a living as a hotel porter and bank janitor in Raleigh. Tragically, Jacob died while trying to save two of his wealthy employers from drowning when Andrew was three years old. His widowed mother worked as a weaver and a spinner to feed Andrew and his older brother William. She married Turner Daugherty when Andrew was still a boy, though the addition to the family did not much improve family finances. When Andrew was fourteen, his parents apprenticed the two boys to a local tailor, with whom they worked for several years before running away. After being on the run for two years with a reward on his head, Andrew returned to Raleigh in 1826 to reunite with his mother and stepfather before moving west in a one-horse cart to Greeneville, Tennessee, where the seventeen-year-old Andrew set up shop as a tailor.

The young tailor had tried to teach himself to read and write by poring over a book of great orations that he had received as a gift; however, Andrew never mastered the basics of English grammar, reading, or math until he married his wife, Eliza McCardle, age sixteen, in 1827. The only child of the village shoemaker, Eliza had first spotted Andrew and his ragtag family when they pulled into Greeneville looking for work. She told a friend that it was almost love at first sight—on seeing Andrew, she knew that he would be her beau someday. It was a lucky match for Andrew because Eliza, though only a young girl herself, was well educated and had an eye for money. While he sewed and stitched in his little shop, Eliza read to him and taught him to spell and to write. She also taught him to invest his money wisely in town real estate and farmlands.

The young tailor had tried to teach himself to read and write by poring over a book of great orations that he had received as a gift; however, Andrew never mastered the basics of English grammar, reading, or math until he married his wife, Eliza McCardle, age sixteen, in 1827. The only child of the village shoemaker, Eliza had first spotted Andrew and his ragtag family when they pulled into Greeneville looking for work. She told a friend that it was almost love at first sight—on seeing Andrew, she knew that he would be her beau someday. It was a lucky match for Andrew because Eliza, though only a young girl herself, was well educated and had an eye for money. While he sewed and stitched in his little shop, Eliza read to him and taught him to spell and to write. She also taught him to invest his money wisely in town real estate and farmlands.

Political Involvement and Leanings

By 1834, the young Andrew had already served several terms as town alderman and as mayor of Greeneville, identifying with the town's laboring class. At that time, he called himself a Jacksonian Democrat, aligning with the common-man ideology of populist President Andrew Jackson. He liked politics, especially giving stump speeches, and he found that his common-man tell-it-like-it-is style went over well with both the town's mechanics and artisans as well as the rural folk of Washington and Greene counties. His popularity won him election to the state legislature's lower house in 1834 and 1838 and a seat in the state senate in 1841. From 1843 to 1853, Johnson served in the U.S. House of Representatives as a Democrat. Unfortunately, he lost his seat when the district was gerrymandered, or redrawn, to his disadvantage following the census of 1850. Johnson then served two terms as governor of Tennessee from 1853 to 1857. When the Civil War broke out, Johnson was a first-term U.S. senator, elected unanimously as a Democrat by the Tennessee legislature.

As a politician, Johnson supported Jacksonian policies, though he often took positions that seemed contradictory at first glance. He opposed, for example, federal funding of internal improvements yet strongly advocated homestead legislation granting free western lands to settlers. Johnson raged against the interests of his state's planter class even to the point of wanting to create a separate mountain state from the poorer up-country regions of Tennessee, Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia. Yet he supported the Compromise of 1850 and the gag rule that prevented the consideration of antislavery petitions before the House of Representatives. Both of these positions were usually identified with the "slavocracy," whom he hated. Johnson threw his weight behind the annexation of both Texas and Oregon, Stephen Douglas's Kansas-Nebraska Act, the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, and the presidential candidacy of John C. Breckinridge in 1860. These political choices put Johnson firmly in the states' rights, proslavery wing of the Democratic Party.

On the other hand, he had no tolerance for any talk of breaking up the Union. Furthermore, he criticized President James Buchanan for not dealing sternly and swiftly with the Southern rebels during the last months of his administration. He believed that the secessionist movement was a conspiracy of the planter elite and had to be stopped by force if necessary. Additionally, Johnson attacked anti-Catholic prejudice and championed religious freedom but filled his own political speeches with vile racist language against blacks.

Risking Life and Fortune

When Southern secessionists formed the Confederacy after Abraham Lincoln's 1860 presidential election, Johnson struggled to keep Tennessee in the Union. He warned his constituents that the dissolution of the United States would result in anarchy and a patchwork of "petty little governments, with a little prince in one, a little potentate in another, and a republic somewhere else." When Tennessee left the Union, Johnson, in line with his area in eastern Tennessee, broke with his state and was the only Southern senator not to resign his seat in the U.S. Senate. Unable to get back to his family in Tennessee, Johnson became one of the strongest supporters of President Lincoln, objecting to any compromise with the Confederacy as long as the rebels were in charge. In the South, Johnson was deemed a traitor and hung in effigy in his hometown. His properties were confiscated, and his wife and two daughters were essentially driven from the state with little more than what they could carry in a wagon. In the North, Johnson's stand made him an overnight hero, praised in the press as a true patriot who had risked his life and his fortune to side with the Union in the Civil War.

Following Union military victories in Tennessee, President Lincoln appointed Johnson the military governor of the state, with the rank of brigadier general. Empowered to discharge executive, legislative, and judicial functions, Johnson ruled with a heavy hand. He arrested critics of the federal government and held them without trials; such critics included clergymen who supported the Confederacy in their sermons. Johnson also dismissed state officeholders who were unwilling to denounce secession, closed anti-Union newspapers, seized all railroads in the state, supervised military operations from Nashville, and levied heavy taxes on planters and large landholders. At Governor Johnson's personal appeal, Lincoln exempted Tennessee from the Emancipation Proclamation, making it the only rebel state in which the proclamation did not apply at least in part. Johnson put emancipation as a low priority compared to preserving the Union because he did not want to alienate loyal whites who resented talk of freeing the slaves, especially the small farmers and artisans who feared former slaves competing with them for land and work. By the end of the Civil War, Johnson's actions had restored civil government to Tennessee.

The Campaign and Election of 1864

Uncertain about his chances for reelection in 1864, President Lincoln tried to balance the ticket by convincing Republican delegates to their National Union Convention to drop Hannibal Hamlin of Maine as vice president in favor of Andrew Johnson, who was the most prominent "War Democrat" in the nation. Moderate Republicans eagerly supported Johnson, who was known for his tough stand against the planter aristocracy, although Hamlin lobbied hard to retain his place on the ticket. The move shrewdly countered the appeal of "Copperheads" or "Peace Democrats," who found it difficult to portray Lincoln as anti-Southern or as a tool of the abolitionists with Johnson as his running mate. Johnson also strengthened Lincoln's appeal to the Union's working class, especially the Irish. The Irish Catholic voters favored Johnson for his strong record of opposing anti-Catholicism while governor of Tennessee.

Additionally, he was a widely recognized champion of the nation's so-called yeoman Democrats, a term that embraced small farmers and village artisans everywhere in the Union. But there were some Radical Republicans who felt differently. Thaddeus Stevens grumbled in the Senate that the Republicans should have found a candidate "without going down into one of those damned rebel provinces." Other Radical Republicans had called a convention in Cleveland and nominated John Frémont for the presidency and General John Cochrane for the vice presidency, but with Johnson on the ticket, Lincoln's hand was strengthened with moderates even as he lost support from the right wing of his party.

The Lincoln-Johnson ticket, opposed by Democratic candidate General George B. McClellan of New Jersey and Ohio Democrat George H. Pendleton, went into the election with several advantages: Most rank-and-file Republicans greatly supported Lincoln and his determination to win the war. So too did most Union soldiers, even though McClellan, whom Lincoln had dismissed because he felt that the general was unwilling to decisively engage the Confederate forces of General Robert E. Lee in the Virginia theater, was popular with most bluecoats. Also, McClellan rejected the peace plank of his own party platform, which called for immediate cessation of hostilities and the restoration of peace "on the basis of the Federal Union of States." Most importantly, when General William Sherman successfully marched through Georgia in September, delivering Atlanta to Lincoln as an election present, the sentiment for Lincoln united the party behind him. Lincoln was reelected in a landslide victory in which he earned ten times more electoral college votes than McClellan.

The Campaign and Election of 1866

Although not a presidential election, the off-year congressional election of 1866 was in fact a referendum election for Andrew Johnson. By the summer of 1866, Johnson had lost support within the Republican Party for his Reconstruction policies. (See the Domestic Affairs section for details.) After a unity meeting of 7,000 delegates at the National Union Convention—which met in Philadelphia on August 14—failed to bridge the growing gap between Johnson and the Republicans, the determined President decided to take the issue to the people.

Beginning on August 28, accompanied by such notables as Civil War hero Admiral David Farragut, Johnson launched an unprecedented speaking tour in the hopes of regaining public and political support. He traveled from Philadelphia to New York City, then through upstate New York and west to Ohio before heading back to Washington, D.C. This "swing around the circle" was marked by an intemperate campaign style in which Johnson personally attacked his Republican opponents in vile and abusive language reminiscent of his Tennessee stump speech harangues. On several occasions, it also appeared that the President had had too much to drink, nearly stumbling from the platform. In the end, the campaign was a disaster for Johnson. One observer later said that the President lost one million Northern voters as a result of his tour. In the election, the anti-Johnson Republicans won two-thirds of both houses, thus sealing Johnson's doom and giving his opponents enough power to override his programs. Later, the House of Representatives, in voting its articles of impeachment against Johnson, would charge him with disgracing his office by attempting to appeal directly to the people for support in the 1866 elections—something that was considered to be demagogic and beneath the dignity of a President at the time.

The Campaign and Election of 1868

Having escaped being convicted in his May 1868 impeachment trial by one vote, Johnson had no chance of being reelected as President. (See the Domestic Affairs section for details.) He attempted to win the Democratic nomination at the convention in the newly completed Tammany Hall in New York. He told his supporters that a united Democratic Party, with him at its helm, stood the best chance of blocking the drive for black political equality in the South. At the convention, Johnson came in second in the balloting on the first vote, trailing first-place leader George H. Pendleton of Ohio 105 to 65. After that ballot, which was a face-saving vote for Johnson by the Democrats, the incumbent President never surfaced again. Instead of Johnson, the Democrats ran Horatio Seymour, the former wartime governor of New York, who was the presiding officer of the convention, and Francis P. Blair of Missouri. The Republicans bitterly attacked Johnson as a traitor to Lincoln and the nation in their convention in Chicago, nominating General Ulysses S. Grant and House Speaker Schuyler Colfax of Indiana as President and vice president, respectively. Running a "bloody shirt" campaign, which tagged the Democrats as the party of secession and treason, the Republicans swept to victory, winning 53 percent of the popular vote to Seymour's 47 percent. (See Grant Biography, Campaigns and Elections section, for further details.) Johnson took a little active role in the campaign for Seymour.

On April 15, six weeks after Andrew Johnson was sworn in as vice president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. Had the assassin's plot gone as planned, Johnson, Ulysses S. Grant, and Secretary of State William Seward would have also been killed. As it turned out, co-conspirator George Atzerodt had stalked the vice president but lost his nerve at the last minute. Johnson, who was staying at the Kirkwood House, rushed to Lincoln's bedside when he was told of the attack. A few hours after Lincoln's death, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase swore Johnson in as President of the United States. Republicans were relieved that Johnson had not been killed and could provide continuity; they thought that he would be putty in their hands and would follow the dictates of Republican congressional leaders.

Although Johnson came into the presidency with much political and administrative experience, the task confronting him would require extraordinary talents of leadership that Johnson had yet to exhibit. Most immediate was the question of what to do with the defeated Confederate states—that is, what rights would be granted the 4 million former slaves, and what punishment, if any, would be applied to the supporters of the Confederacy? Just prior to Lincoln's death, indeed the very morning of his assassination, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton had presented to Lincoln's cabinet the outlines of a reconstruction program. The program would impose military rule and stiff conditions upon the defeated Southern states for their restoration to the Union. This represented a substantial modification of Lincoln's earlier stand urging a quick return to equal status with few conditions beyond oaths of loyalty and the abolishment of slavery. Although Lincoln favored granting voting rights to black men with property and education, he had not been prepared to force the issue, which aroused intense opposition and concern among Radical Republicans within his own party.

The Question of Black Suffrage

In the minds of most Republicans, there were three related problems to Lincoln's easy no-strings-attached postwar policy toward the Confederate states. First, the defeated states would certainly take advantage of the freed slaves to impose racial strictures and labor conditions that would keep intact the economic and political power of the old planter class. This situation would enable the South to continue its obstructionist role in Congress and opposition to federal programs benefiting industrial and western interests. Secondly, unless Southern blacks were enfranchised and Confederate leaders disfranchised, a united Democratic Party might win the congressional elections in 1866 and then run and elect someone like Robert E. Lee to the presidency in 1868. As a new party, the Republicans understood how fragile their hold on government was. In a fully restored Union, the black vote was considered essential to continued Republican control of the White House and Congress. And thirdly, the presence of black soldiers stationed in Southern states, the intense expectations of the former slaves for full civil rights, and the demands of abolitionist reformers, such as Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner and Frederick Douglass, for racial equality could not be ignored easily.

At first, many Radical Republicans had assumed that Johnson shared their broad and expansive concept of federal power and their commitment to political equality for blacks. In this, they were mistaken. Although a strong Union man, Johnson had always believed in a strict construction of the Constitution and in states' rights, which did not include the rights of secession. He followed Lincoln's earlier reasoning that while individual "traitors" should be punished, the states had never legally left the Union nor surrendered their rights to govern their own affairs. Indeed, he echoed Lincoln's view that 600,000 dead soldiers had determined the issue that the South had been unable to leave the Union. So how could the Southern states be treated as if they had? In Johnson's mind, the issue of what to do with the defeated Southern states was simple: impose conditions upon their return to full standing, such as the irrevocable abolition of slavery written into their state constitutions and loyalty oaths as a condition of suffrage, but do not impose black suffrage as a condition of readmission.

Phase I: Presidential Reconstruction

From the day of his inauguration until December of 1865, the question of Reconstruction was almost totally in the hands of Johnson because Congress had recessed shortly before he took the oath of office. It did not reconvene until December. In those eight months, Johnson rushed to implement his own Reconstruction policies based upon his interpretation of Lincoln's program. He appointed provisional governors to the defeated states and required them to call special conventions to draft new constitutions that abolished slavery and renounced secession. After the ratification of these constitutions, newly elected governments were to send representatives to Congress, and the states thereby would be restored to the Union. According to his program, every Southern voter would have to swear an oath of loyalty in order to obtain amnesty, or pardon. Several classes of Southerners were not to be given amnesty, however: (1) former federal officials who had supported the Confederacy, (2) graduates of the military academies at West Point or Annapolis who had fought on the side of the rebels, (3) high-ranking Confederate officers and political leaders, and (4) all individuals who had aided the rebellion and owned taxable property valued at more than $20,000. Individuals who fell into these four categories had to apply personally to the President for pardon and restoration of their political rights.

During the summer of 1865, the white residents of every Southern state worked feverishly to abide by Johnson's program so as to be ready to take seats in the U.S. Congress upon its reconvening in December. Surprisingly, Johnson handed out thousands of pardons in almost routine fashion, thus enabling most members of the old planter class and many Confederate leaders to reemerge in power on the state level. In the rush to reenter the Union, some state conventions defiantly refused to reject secession and the Confederate debt. Almost all of these states imposed severe laws that limited the freedom of former slaves. Known as "black codes," these laws required, with variations in each state, former slaves to carry permits on their body when off plantations, to observe curfews in town, and to have signed contracts of employment by the end of January or be arrested as vagrants. These codes were designed to force the former slaves into a slavelike employment status on the plantations. Each youth, for example, was required to be apprenticed to an employer, who could exercise parental authority over their wards. According to law, parental permission was not required, and in many cases, the courts bound young men and women in their twenties as apprentices. Some state conventions disallowed former slaves to own or rent farms. Rights to hunt, carry firearms, fish, or freely graze livestock were typically revoked for blacks. And most state-supported institutions, such as schools and orphanages, excluded blacks completely.

Phase II: Congressional Reconstruction

Not surprisingly, when Congress reconvened in December, the Republican majority established a Joint Committee of Reconstruction to examine Johnson's policies and voted not to admit the newly elected Southern representatives or to recognize the newly reestablished state governments as valid. Thereafter, Congress and the President clashed continually over the next two years. In the ensuing confrontation, the Republican membership in Congress united in support of a military Reconstruction program that would guarantee political and civil rights for Southern blacks. Johnson aided this party unity by his heavy-handed efforts to block black suffrage and congressional programs that he considered a usurpation of presidential authority.

When Congress passed an extension of the Freedmen's Bureau in February of 1866, most Republicans fully expected Johnson to sign it into law. Congress wanted this agency to continue a federal refugee program aimed at protecting and providing shelter and provisions for the displaced slaves as well as trials by military commissions of individuals accused of depriving African Americans of their civil rights. To Congress's surprise, Johnson not only vetoed the bill but he also attacked it as race legislation that would encourage a life of wasteful laziness for Southern blacks. In response, Congress passed this bill five months later over Johnson's veto.

President Johnson also vetoed the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1866, which defined as citizens all persons born in the United States (except Native Americans). The bill also listed certain rights of citizens, including the right to testify in court, to own property, to make contracts, and to enjoy the "full and equal benefit of all laws" and the due process accorded to all citizens. It authorized federal officials to bring suit in federal courts rather than state courts for civil rights violations. Johnson tried to strike down the law as a violation of states' rights, expecting his veto to appeal to antiblack sentiment among Northern voters. In April, Congress passed the act over Johnson's veto—this was the first time that Congress had overridden a veto of major legislation.

As tensions mounted further, Johnson's determination to deny civil rights to African Americans motivated the Joint Committee on Reconstruction to formulate the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. Fearful that the Supreme Court might at some future date rule unconstitutional the Civil Rights Act, Congress passed this far-reaching amendment on June 16, 1866. For the first time, the nation's lawmakers defined national citizenship, which authorized the federal government to protect the rights of U.S. citizens. Congress also revoked the three-fifths clause of the Constitution, and it now provided for a proportionate reduction in representation when a state denied suffrage to any male citizen, except for those who have participated in rebellion or other crimes. When most Southern states rejected the amendment, the Joint Committee made its acceptance a condition of a state's restoration to the Union.

Off-Year Election Showdown

It was in this intense atmosphere that the congressional elections of 1866 loomed large. Southern whites hoped to use the expected popular backlash to Republican militancy to seize control of the House and then overturn the congressional Reconstruction initiatives. Johnson hit the campaign trail in an unprecedented effort to elect congressmen who supported his policies. Johnson's "swing around the circle" backfired on him, however, as his blatant racism came to the forefront in his personal attacks on his opponents, offending many Democratic moderates and uncommitted voters. When Republicans won two-thirds control of both houses, the Joint Committee on Reconstruction passed—over the President's veto—the Reconstruction Act of March 8, 1867. This act divided the eleven Southern states—excluding Johnson's home state of Tennessee—into five military districts subject to martial law. To be fully restored to the Union, Southern states were required to hold new constitutional conventions elected by universal manhood suffrage. These conventions would then establish state governments to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment and guarantee black male suffrage. A military governor, who was authorized by Congress, controlled each district with the power to use military force to protect life and property. Once these provisional governments had fully complied with congressional directives, they might be allowed full status in the Union, but Congress reserved the right to decide each case.

On March 2, 1867, Congress moved to limit Johnson's powers as President in several ways. The Command of the Army Act instructed the President to issue orders only through the General of the Army, then Ulysses S. Grant, who could not be removed nor sent outside of Washington without Senate permission. This was followed by the Tenure of Office Act, on the same day, which prohibited the President from removing certain federal officials without senatorial approval. It did this by specifying that officials appointed with the advice of the Senate were to remain in office until the Senate approved a successor.

When Southern whites refused to cooperate in the calling of new constitutional conventions, Congress passed a series of supplementary Reconstruction acts from March through July 1867. These new pieces of legislation gave the military commanders broad powers to initiate the calling of the conventions and to declare a convention valid if supported by a majority of the votes cast, thus overriding the white boycott. Union commanders were expected to follow congressional policy and not directives from the commander in chief on this matter. By late 1867, most Southern states held constitutional conventions, and all of them were dominated by Radical Republican "carpetbaggers," Southern "scalawags," and newly franchised Southern blacks. Between June 22 and 25, 1868, seven Southern states—Arkansas, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, and South Carolina—were readmitted by Congress to full status in the Union.

Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

Thoroughly blocked at every turn, Johnson felt he had no choice but to challenge what he considered to be the usurpation of presidential authority in the Tenure of Office Act. Understanding that he risked impeachment, Johnson challenged the act by dismissing Secretary of War Stanton on August 12, 1867, while Congress was out of session. He then named General Grant as interim secretary of war. When Congress reconvened in December, Johnson submitted his reasons to the Senate, but the Senate refused to concur with the dismissal under the provisions of the law. Grant broke with the President. The crisis flared up again, however, on February 21, 1868, when Johnson dismissed Stanton once more. On February 24, 1868, the House voted to impeach Johnson by a vote of 126 to 47 without holding hearings first or having specific charges against him. The House subsequently drew up eleven charges against the President, principally associated with his alleged violations of the Tenure of Office Act and the Command of the Army Act but also including charges that his actions had brought disgrace and ridicule to the presidency.

The managers of the House of Representatives Impeachment Committee presented the articles to the Senate for trial on March 4, and the trial began with opening statements on March 30, presided over by Chief Justice Chase. Johnson's legal counsel argued that Johnson had fired Stanton to test the constitutionality of the Tenure of Office Act and that his action constituted neither a high crime nor a misdemeanor by any sensible definition of the terms. Voting on May 16, the Senate failed to convict Johnson by one vote of the two-thirds necessary—35 votes to 19. Two subsequent ballots on May 26 produced the same results, and the Senate adjourned as a court of impeachment.

The impeachment of Andrew Johnson, the first of only two Presidents to be impeached in U.S. history—the second was President William Clinton—involved complicated issues of law, politics, and personalities. At its heart lay the nearly irreparable relations between Johnson and Congress over which agency of government should oversee Reconstruction. This question of competing authority masked, however, a more fundamental issue: Congress had instructed the U.S. Army to implement a policy that its commander in chief vehemently opposed. In direct violation of congressional intent and the Command of Army Act, Johnson had used the summer of 1867, when Congress was not in session, to remove several military commanders in favor of officers more supportive of white rule in the South. Later, he tried to create an "Army of the Atlantic," headquartered in the nation's capital, as a means of intimidating his opponents in Congress. Seeing that Johnson was using the Army to play politics and thus endangering the lives of soldiers in the field, Grant turned against the President. However, none of the impeachment articles hit at the principal issue: Johnson's loss of support within the majority congressional party. Had the nation been governed by a parliamentary system, which requires a prime minister to have the support of a majority of the legislature, Johnson would have been summarily removed in a vote of no confidence. Almost all Republicans agreed that Johnson was totally unfit for office.

But these were not clearly impeachable offenses, and this uncertainty worked in his favor. Also, because no vice president had been elected after Johnson's ascent to the presidency, his successor would be Benjamin Wade, president pro tem of the Senate, an extreme radical on Reconstruction and a soft-money, pro-labor politician feared by many Northern businessmen. With Senator Wade in the wings, many Johnson opponents were hesitant about voting to convict, especially those who thought that if Wade assumed the presidency, he might try for the nomination in 1868, thus blocking General Grant. Also, Chief Justice Chase refused to allow deviation from the charges to discuss or include broader issues of policy.

In the end, the seven Republicans who voted to acquit—most of them supporters of Grant—were silently supported by their moderate party colleagues. Had these seven not indicated a willingness to acquit, others stood ready to change their votes. Many Senate Republicans had decided to make it a close vote but not a conviction, especially once it became clear that if Johnson was acquitted, he was prepared to cease his obstructionist ways for the rest of his term and stop his interference with Reconstruction and with the military commanders and the War Department.

The final vote maintained the principle that Congress should not remove the President from office simply because its members disagreed with him over policy, style, and administration of office. But it did not mean that the President retained governing power. For the rest of his term, Johnson was a cipher without influence on public policy. Moreover, between his presidency and the turn of the century, a "weak presidency" system of governance was instituted, one which Woodrow Wilson referred to in the 1870s as "Congressional Government" because after the Johnson collapse, the country was really run by congressional committee leaders and cabinet secretaries. The ex-President did, however, return to the Senate in 1875.

Foreign Affairs

Although Andrew Johnson's presidency was marked by significant chaos and administrative ineptitude on the home front, its foreign affairs were ably managed by Secretary of State William H. Seward. In 1866, the Russian minister to the U.S. indicated that Czar Alexander II might be willing to sell Russian holdings in North America—nearly 500,000 square miles. Seward offered $7.2 million, which was two cents an acre, and the Russians accepted, transferring land that would become Alaska to the United States.

The treaty of sale differed from earlier territory arrangements by not promising eventual statehood. Its inhabitants—except for Indians—would become American citizens immediately, but it left open the question of statehood, thus relegating the new territory to the status of a colonial possession. Some critics ridiculed the purchase as a frozen, worthless wasteland, as "Seward's Folly." But the Senate embraced the sale with enthusiasm. Charles Sumner, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, viewed the purchase as a step leading toward the ultimate possession of Canada. Seward himself wanted the U.S. to annex much of the Northern Hemisphere, but he was unable to gain Senate consent to acquire the Virgin Islands, Hawaii, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Greenland, or Iceland.

Forcing the French from Mexico

At the end of the Civil War, Mexico was embroiled in war. A French army had occupied key parts of Mexico in 1861, installing a puppet ruler, Archduke Maximilian of Austria, as emperor. The Mexican government, led by Benito Juárez, resisted the forces of Napoleon III yet had little decisive effect. As soon as the American Civil War ended, Secretary of State Seward sent 50,000 battle-tested U.S. soldiers to the Mexican border to back up his demand that Napoleon withdraw all of his forces. Napoleon agreed, and the last French soldier left in 1867. Although the Monroe Doctrine was never mentioned by name, the confrontation reinforced its hold on American foreign policy, especially in later years when the U.S. used it as a precedent for resisting European efforts to construct a Panamanian canal in Central America.

Relations with Great Britain

During the Johnson presidency, the bumpy U.S. relations with Great Britain were repaired. Johnson tamped down a crisis by enforcing neutrality laws against Irish American Fenians, who made several armed attacks in Canada in an attempt to annex Canadian territory, then controlled by Great Britain. Civil War claims against the British for building Confederate warships that had sunk Union shipping were sent to arbitration.

Family Life

Life in the White House for Andrew Johnson's family was an ongoing cavalcade of visitors and activity. Because his wife, Eliza, was a semi-invalid and kept to her room most of the time, suffering from tuberculosis, Johnson asked his two daughters, Martha and Mary, a widow, to live in the White House and serve as official hostesses. They brought their five children and Martha's husband, David T. Patterson, who later became a U.S. senator from Tennessee, with them.

Johnson's sons were tragic figures: The oldest, Charles, died in 1863 after being thrown from a horse. He was serving at the time with the Middle Tennessee Union Infantry as an assistant surgeon. Johnson's next son, Robert, suffered from alcoholism. His drunken escapades led to his retirement from the First Tennessee Union Cavalry, after which he served as Johnson's private secretary. He died from his affliction in 1869 at age thirty-five. The youngest boy, Andrew Jr., a teenager during the White House years, liked to write and tried his hand at journalism after the war, founding the Greeneville Intelligencer. It failed after two years, and he died soon after at age twenty-seven.

No clearly established routine dominated daily life in the White House. The President rose early and worked late. He was not a religious man, although he sometimes attended Methodist services with his wife. He liked best the Baptist faith because of its democratic structure. But he also admired Catholic services because all Catholics had equal access to church pews regardless of their money.

For entertainment, Johnson practiced politics, talked for hours with old friends who would come to visit, played an occasional game of checkers, and enjoyed circuses and minstrel shows. He probably took some of his racist banter on the stump from the humor poked at blacks in the popular minstrel shows of the day. He also enjoyed drinking Tennessee bourbon, and he suffered from perhaps an undeserved reputation for overindulging. At the grand inauguration ball in 1864, Johnson, while suffering from a severe cold and fever, had taken a whiskey just before making his formal speech. He looked and sounded drunk to the embarrassment of his family and President Lincoln. At several other times during his presidency, Johnson appeared in public in what looked to be an inebriated state. He never lived these incidents down, although historians contend that they were greatly exaggerated.

The American Franchise

During Andrew Johnson's presidency, the composition of the American electorate underwent revolutionary change. The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, in conjunction with congressional Reconstruction, set the stage for extending suffrage to hundreds of thousands of African American males. Congress did this indirectly, however, threatening to penalize states that did not enfranchise African Americans by reducing their congressional and electoral representations in proportion to the adult males disfranchised. But the amendments did not specifically guarantee suffrage to African Americans. It would take the Fifteenth Amendment, approved by Congress in 1869 and ratified in 1871, to actually guarantee voting rights to African American males. It prohibited the federal government or any state from restricting the right to vote because of a person's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude." More important in extending suffrage to formerly enslaved males during the Johnson years were the actions undertaken under the Reconstruction Acts of 1867, which required African American male suffrage as a condition of a state's readmission to the Union.

Black Political Participation

In the state constitutional conventions that met in 1868, 265 black delegates were included. In Louisiana and South Carolina, half or more of the delegates were black. Starting in 1869 and lasting until 1877, fourteen African American men served in the U.S. House of Representatives, and two African Americans served in the U.S. Senate, Hiram R. Revels and Blanche K. Bruce from Mississippi. Six blacks served as lieutenant governors, and over 600 black men served in Southern state legislatures. Moreover, in heavily black populated counties, African American men were elected to every village, town, and county post from tax collector to mayor.

The upsurge of black political activity was met with terrorist tactics implemented by Southern whites to intimidate both black and white Southern Republicans. Beginning in late 1866, a terrorist organization, the Ku Klux Klan, which was a secret veterans' club, spread through the South. It practiced nighttime harassment, whippings, torture, and even murder. The Klan attacked the white schoolteachers of black children; the Union League Clubs, which organized black voters; and anyone suspected of supporting Republicans. In 1868, one-tenth of the black delegates to the state constitutional conventions had been attacked. When Johnson left office, in much of the South, especially in counties dominated by white majorities, terror had become a common aspect of race relations.

Women's Suffrage Movement

Although black male suffrage increased substantially by 1868, not all reformers were happy with the Fourteenth Amendment. Advocates of women's suffrage objected to the exclusion of women from the amendment, pointing out that it introduced the word "male" for the first time into the Constitution. The amendment, when followed by the Fifteenth Amendment, left feminist leaders feeling betrayed. Thereafter, many women activists severed their historic alliance with the cause of civil rights for African Americans and created an autonomous feminist movement independent of the existing reform crusades. More and more, feminist leaders equated suffrage with liberation from all male dominance and also viewed it as an expression of equality in the voting place.

Neither Republicans nor Democrats intended to do anything about expanding the franchise to women. At the Democratic Convention of 1868, a petition was read from Susan B. Anthony, a leader of the Women's Suffrage Association. She asked the convention to acknowledge the principle of women's suffrage. The delegates roared with laughter, refused to take the petition seriously, and then adjourned for the day in general merriment.

Impact and Legacy

For the most part, historians view Andrew Johnson as the worst possible person to have served as President at the end of the American Civil War. Because of his gross incompetence in federal office and his incredible miscalculation of the extent of public support for his policies, Johnson is judged as the greatest failure of all Presidents in making a satisfying and just peace. He is viewed to have been a rigid, dictatorial racist who was unable to compromise or to accept a political reality at odds with his own ideas. Instead of forging a compromise between Radical Republicans and moderates, his actions united the opposition against him. His bullheaded opposition to the Freedmen's Bureau Bill, the Civil Rights Act of 1866, and the Fourteenth Amendment eliminated all hope of using presidential authority to affect further compromises favorable to his position. In the end, Johnson did more to extend the period of national strife than he did to heal the wounds of war.

Blinded by his personal sense of self-grandiosity, his stubborn disregard for political realities, and his blatant racism, Johnson greatly undermined the office of the presidency and is held personally responsible for the victory of congressional authority in conflict with presidential authority. His political ineptitude enabled congressional activists to succeed in imposing presidential restraint upon the chief executive, thus giving to Congress the power to set national policy for the next thirty-five years.

Most importantly, Johnson's strong commitment to obstructing political and civil rights for blacks is principally responsible for the failure of Reconstruction to solve the race problem in the South and perhaps in America as well. Johnson's decision to support the return of the prewar social and economic system—except for slavery—cut short any hope of a redistribution of land to the freed people or a more far-reaching reform program in the South.

Historians naturally wonder what might have happened had Lincoln, a genius at political compromise and perhaps the most effective leader to ever serve as President, lived. Would African Americans have obtained more effective guarantees of their civil rights? Would Lincoln have better completed what one historian calls the "unfinished revolution" in racial justice and equality begun by the Civil War? Almost all historians believe that the outcome would have been far different under Lincoln's leadership.

Among historians, supporters of Johnson are few in recent years. However, from the 1870s to around the time of World War II, Johnson enjoyed high regard as a strong-willed President who took the courageous high ground in challenging Congress's unconstitutional usurpation of presidential authority. In this view, much out of vogue today, Johnson is seen to have been motivated by a strict constructionist interpretation of the Constitution and by a firm belief in the separation of powers. This perspective reflected a generation of historians who were critical of Republican policy and skeptical of the viability of racial equality as a national policy. Even here, however, apologists for Johnson acknowledge his inability to effectively deal with congressional challenges due to his personal limitations as a leader.

American Presidency

The young tailor had tried to teach himself to read and write by poring over a book of great orations that he had received as a gift; however, Andrew never mastered the basics of English grammar, reading, or math until he married his wife, Eliza McCardle, age sixteen, in 1827. The only child of the village shoemaker, Eliza had first spotted Andrew and his ragtag family when they pulled into Greeneville looking for work. She told a friend that it was almost love at first sight—on seeing Andrew, she knew that he would be her beau someday. It was a lucky match for Andrew because Eliza, though only a young girl herself, was well educated and had an eye for money. While he sewed and stitched in his little shop, Eliza read to him and taught him to spell and to write. She also taught him to invest his money wisely in town real estate and farmlands.

The young tailor had tried to teach himself to read and write by poring over a book of great orations that he had received as a gift; however, Andrew never mastered the basics of English grammar, reading, or math until he married his wife, Eliza McCardle, age sixteen, in 1827. The only child of the village shoemaker, Eliza had first spotted Andrew and his ragtag family when they pulled into Greeneville looking for work. She told a friend that it was almost love at first sight—on seeing Andrew, she knew that he would be her beau someday. It was a lucky match for Andrew because Eliza, though only a young girl herself, was well educated and had an eye for money. While he sewed and stitched in his little shop, Eliza read to him and taught him to spell and to write. She also taught him to invest his money wisely in town real estate and farmlands.