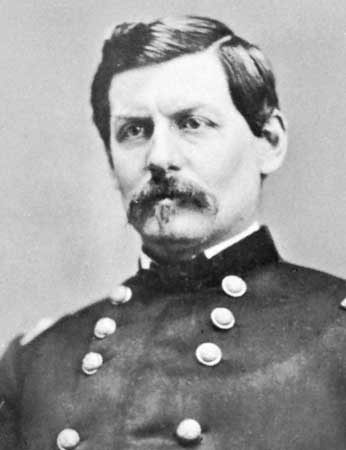

George B. McClellan (1826-1885)

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 - October 29, 1885) was a Major General of the Union Army during the American Civil War. He played an important role in raising a well trained and organized army for the Union, but his leadership skills in battle were questioned, and he was accused of being incompetent and overly cautious. While skilled in organization, he did not seem to have the decisive drive of Lee, Grant, or Sherman, willing to risk a major battle even when all preparations were not perfect. He also seemed never to grasp that he needed to maintain the trust of President Abraham Lincoln, but instead proved to be frustratingly insubordinate to his Commander in Chief.

Early career

Born in Philadelphia, McClellan first attended the University of Pennsylvania, then transferred to West Point, graduating second in his class of 1846. Originally assigned to the engineers, he served under Winfield Scott in Mexico, then transferred to the cavalry in 1855.

Dispatched to study European armies, he observed the siege of Sevastopol in the Crimean War. He then adapted a saddle used in Prussia and Hungary into the "McClellan Saddle," which became standard issue for as long as the U.S. horse cavalry existed. McClellan resigned his commission January 16, 1857, and got into the railroad business, becoming chief engineer of the Illinois Central and then eventually division president of the Ohio & Mississippi. He rejoined the military when war broke out in 1861, initially commanding the Ohio Militia. His first combat assignment was to occupy the area of western Virginia, which wanted to remain in the Union and later became the state of West Virginia. He defeated there two small Confederate armies in 1861 and became famous throughout the country.

The Civil War

After the defeat of the Union forces at Bull Run in July 1861, Lincoln appointed McClellan commander of the Army of the Potomac (July 26), the main Union army located around Washington. He brought a much higher degree of organization to this army, and on November 1, 1861 he became supreme commander over all Union armies after General Winfield Scott's retirement. In late 1861 and early 1862, many became impatient with McClellan's slowness to attack while he insisted the troops were still not ready. Lincoln urged McClellan to attack and accepted (with some reluctance) McClellan's plan to advance on Richmond from the southeast after moving by sea to Fort Monroe, Virginia (a fort that stayed in Union hands when Virginia seceded). This campaign is known as the Peninsula Campaign. Lincoln removed McClellan from the supreme command of all Union armies in mid-1862 while leaving him in command of the Army of the Potomac.

McClellan's advance up the Virginia Peninsula proved to be slow. He believed intelligence reports that credited the Confederates with two or three times the men they actually had. Critics of his slowness felt justified when some of the Confederate fortifications, evacuated after McClellan took the time to bring up siege artillery against them, proved to be lined with fake cannons. The Confederate general John B. Magruder also exploited McClellan's caution by marching a group of men over and over again past places where they could be observed, to give the impression of a long line of troops arriving.

McClellan also placed hopes on a simultaneous naval approach to Richmond via the James River. That approach proved flawed following the Union Navy's defeat at the Battle of Drewry's Bluff about 7 miles downstream on May 15, 1862. McClellan came within a few miles of Richmond, Virginia and on June 1, his army repelled an attack at Seven Pines. Confederate commander Joseph E. Johnston was wounded in this battle, and Jefferson Davis named Robert E. Lee commander of the Army of Northern Virginia. McCllellan spent the next 3 weeks repositioning his troops and waiting for promised reinforcements, losing valuable time while the Confederates newly placed under Robert E. Lee beefed up Richmond's defenses.

At the end of June, Lee ordered a series of attacks in the Seven Days Battles. While these attacks failed to attain Lee's goal of crushing McClellan's army, they destroyed McClellan's nerve and convinced him to withdraw his army further from Richmond to a base on the James River. In a telegram reporting on these events, McClellan accused Lincoln of doing his best to see that the Army of the Potomac was sacrificed, a comment that Lincoln never saw (at least at that time) because it was censored by the War Department telegrapher.

Urged to remove McClellan from command, Lincoln compromised by taking some of McClellan's men and some newly organized units to create the Army of Virginia under John Pope, who was to advance towards Richmond from the northeast. Pope was beaten spectacularly by Lee at Second Bull Run in August.

Lee then advanced into Maryland, hoping to arouse pro-Southern sympathy since Maryland was a slave state. Lincoln then restored Pope's army to McClellan on September 2, 1862. Union forces accidentally found a copy of Lee's orders dividing his forces, but McClellan did not move swiftly enough to defeat in detail the Confederates before they were reunited. At the Battle of Antietam near Sharpsburg, Maryland, on September 17, 1862, McClellan attacked Lee. Lee's army, while outnumbered, was not decisively defeated, because the Union forces did not manage to coordinate their attacks and because McClellan held back a large reserve.

After the battle, Lee retreated back into Virginia. When McClellan failed to pursue Lee aggressively after Antietam, he was removed from command on November 5 and replaced by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside on November 9. He was never given another command.

McClellan generally had very good relations with his troops. They referred to him affectionately as Little Mac; others sometimes called him the Young Napoleon. It has been suggested that his reluctance to enter battle was caused in part by an insistent desire to spare his men, to the point of failing to take the initiative against the enemy and therefore passing up good opportunities for decisive victories, which could have ended the war early and thereby could have spared thousands of soldiers who died in those subsequent battles. Another cause could have been personal bravery. During critical battles, McClellan generally stayed well away from any action. During the Seven Days, he kept himself far away from the scenes of battle north of the Chickahominy River. At the Battle of Malvern Hill, he was on a Union gunboat, the U.S.S. Galena, at one point ten miles away down the James River. At Antietam, his headquarters was miles to the rear and he had little control over the battle.

Civilian career

McClellan would go on to run against Abraham Lincoln in the 1864 U.S. presidential election. In the summer of 1864 Lincoln feared that he would lose the election because of weariness with the war, as Grant appeared deadlocked with Lee in Virginia. Sherman's capture of Atlanta, Georgia and Sheridan's victories in the Shenandoah valley dispelled much of this weariness and Lincoln won the election handily. While McClellan was highly popular among the troops when he was commander, it appears that they voted for Lincoln over McClellan in greater proportion than the general population.

After the American Civil War, McClellan was appointed chief engineer of the New York City Department of Docks. In 1872, he was named the president of the Atlantic & Great Western Railroad, and became involved in the South Improvement Company rate-rebate scheme of John D. Rockefeller Jr. who was developing Standard Oil.

Also in 1872, McClellan was among the many investors who were deceived by Philip Arnold in a famous diamond and gemstone hoax.

McClellan was elected Governor of New Jersey in 1877, serving from 1878 to 1881. He died in 1885 at Orange, New Jersey, and is buried at Riverview Cemetery in Trenton. His final years were devoted to traveling and writing. He justified his military career in McClellan's Own Story, published in 1877.

His son, George B. McClellan, Jr., was also a politician.