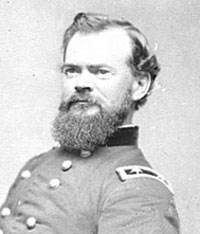

James Birdseye McPherson (1828-1864)

James Birdseye McPherson (November 14, 1828 - July 22, 1864) was a general who fought in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He was killed at the Battle of Atlanta.

James Birdseye McPherson was born November 14, 1828 near Clyde, Ohio and entered West Point in 1849. He graduated in 1853 first in his class from West Point along with his roommate, John Bell Hood, who took command of the Confederate forces he was opposing five days before the time of his death.

At the start of the Civil War, he was stationed in San Francisco, California, but requested a transfer to the Corps of Engineers, rightly thinking that a transfer to the East would further his career. He left San Francisco on August 1, 1861, bound for Washington. He arrived in New York and was notified to report to Boston with a commission as Captain in the Corps of Engineers. In November of 1861, he wrote Halleck in St Louis requesting to be transferred to his command and exchange places with one of Halleck's staff members, a Captain Blunt. Halleck requested that McPherson be allowed to join his staff as aide-de-camp and assistant chief engineer, and ordered McPherson to report at once.

McPherson's career began rising after this assignment. He was the Chief of Engineers (after being promoted to lieutenant colonel) under Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant's army and was responsible for selecting the deployment positions for Grant's troops for their attacks on Fort Donelson and Fort Henry. Following the Battle of Shiloh, he was promoted to Brigadier General of Volunteers in May 1862. On October 8, 1862, he was promoted to Major General. In December 1862, the Army of the Tennessee was divided into five corps; 13th Corps under McClernand, 14th Corps under Thomas, the 15th Corps under Sherman, the 16th Corps under Hurlburt, and the 17th Corps was to be commanded by McPherson. On March 12, 1864, he was given the command of the Army of the Tennessee, after its former commander, Major General William T. Sherman, was promoted to command of all Armies in the West (after Grant was sent to the East). His army was the Right Wing, along with the Army of the Cumberland and the Army of the Ohio consisting the rest of the Union force.

On May 5, 1864, Sherman began his march to Atlanta with McPherson's Army of the Tennessee to be the right wing of his army. McPherson from his engineering studies of the area, knew that North Georgia would be rough country for the movement of troops. Here and there one found bare, perpendicular surfaces, such as Rocky Face Ridge, though more generally, the mountain sides were more sloping, with considerable amount of dense woods and undergrowth. Artillery and supply wagons would be able to move only through passes and gaps in the mountains. Roads were few and most of the countryside was an undeveloped frontier. Local residents referred to the northern third of the state as "Cherokee Georgia" for thirty years prior to the war, the Cherokees were the primary residents of the area.

Sherman planned to have the bulk of his forces feint toward Dalton, Georgia, while McPherson would bear the brunt of Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston's attack, and attempt to trap them. Thomas with his Army of the Cumberland and Schofield with his Army of the Ohio were to advance to Dalton and McPherson was to proceed to Resaca via Snake Creek Gap. Sherman's plan was to force Confederate General Joe Johnston out of his stronghold at Dalton while McPherson was to move south on his west flank and attack the railroad in Johnston's rear. Johnston then would move south to avoid this danger and thus be caught between McPherson's forces in the south, and Thomas and Schofield's forces to the north. Thomas knew McPherson's 24,000 men were to few for him to successfully carry out Sherman's plan and asked to advance on Resaca to give McPherson a larger force, but was not given permission to do so.

At Resaca, McPherson learned that Johnston had cut a road through the woods and was marching his 60,000 troops down upon McPherson's 24,000 men. Mac knew that the success in his mission was in the speed with which his movements could be made. He ordered Maj. Gen. Dodge to attack Resaca at once; while with the 15th Army Corps, guard the column against Johnston's threatening attack. Brig. Gen. Thomas Sweeny commanded Dodge's advance, however was extremely slow in getting his troops to move, and Dodge's forces finally moved forward "with little spirit, making but a weak attack" as one staff officer reported the movement. Dodge then reported to Mac that the enemy had more troops outside of their defensive works than he had in his division. For this failure to try to trap Johnston, Sherman blamed McPherson for being a little too cautious. The initial fault of the movement was not McPherson's caution but in Sherman's decision to use the bulk of his army in a feint movement at Dalton and committing McPherson's small army to bear the burden of Johnston's attack. Sherman would never admit to nor acknowledge this error in his planning.

As the Confederate forces moved southward, McPherson's troops followed vigorously, attacking them at Calhoun and repeatedly attacking them until he reached Kingston, were he was forced to halt due to lack of supplies. He resumed his march upon being resupplied, turning westward to avoid Allatoona Pass, drawing near Pumpkinvine Creek, where once again he attacked the enemy. Sherman sent orders for McPherson to attack the enemy at Dallas, but by the time the courier arrived with this order, Mac had already attacked the enemy, and had driven him through Dallas and a mile beyond. Every time Sherman moved, Joe Johnston met him with checking movements. Johnston faced Sherman step by step until they confronted each other at Kennesaw Mountain. The battle there lasted for a month with disastrous results for the Union Army. On the 27th of June, Sherman made a massive attack on Kennesaw with all his army. McPherson's troops went directly up the mountain and were met with tremendous fire from the Rebel breastworks. The assault failed. On July 2nd, McPherson tried a flanking movement on Johnston's right, but Johnston discovered the movement and fell back, allowing McPherson to occupy Marietta. From the beginning of the campaign, Johnston and McPherson had anticipated each other's movements and craftily circumventing them, each playing the part of a cunning adversary.

However, on July 17, President Jefferson Davis removed Johnston (who had been doing rather decently against the Union armies), and placed old West Point roommate, John Bell Hood in his place.

Hood's first engagement against Union troops as commander, was north of Atlanta at Peachtree Creek. On July 20 Hood was defeated and moved his forces into Atlanta. Meanwhile, McPherson advanced from Decatur meeting little opposition so that in the afternoon of the July 21, he had captured the outer earthworks guarding Atlanta and held the high ground on Bald Hill overlooking Atlanta.

That night, Hood sent Hardee with four divisions south and then to circumvent around McPherson's forces. On July 22 Sherman felt due to the lack of enemy in front of him, that Hood had evacuated Atlanta, and ordered an advance. But McPherson knew his old roommate and knew he wouldn't give up Atlanta without a strong fight. If Atlanta was void of large concentrations of enemy troops, McPherson believed, and rightly so, that Hood planned to attack the Union rear and side.

McPherson was discussing this possibility with Sherman at Sherman's headquarters. Suddenly they heard a large concentration of gunfire from the direction of Decatur. Four Confederate divisions under Lieutenant General William Hardee had flanked Major General Grenville Dodge's XVI Corps. McPherson jumped on his horse and sped towards his troops. He found Grenville Dodge's corps struggling against a fierce assault. After giving orders to Dodge, he followed a line of the 16th Corps towards the 17th Corps, traveling only with his orderly. Entering the woods that separated the two corps, he had traveled only about one hundred fifty yards when a cry of "Halt!" rang out. He stopped for an instant and saw a line of gray skirmishers, wheeled his horse, raised his hat, and made a quick dash to his right. The skirmishers let go with a volley. McPherson staggered in the saddle for a short distance and then fell to the ground.

Like Confederate General Leonidas Polk who was killed by Union cannon fire on June 14th, McPherson was loved by his troops, his commander, and by those who knew him. He was planning to get married to his fiance Emily Hoffman when he could get a furlough. John Bell Hood wrote:

His adversary, John Bell Hood, wrote: "I will record the death of my classmate and boyhood friend, General James B. McPherson, the announcement of which caused me sincere sorrow. Since we had graduated in 1853, and had each been ordered off on duty in different directions, it has not been our fortune to meet. Neither the years nor the difference of sentiment that had led us to range ourselves on opposite sides in the war had lessened my friendship; indeed the attachment formed in early youth was strengthened by my admiration and gratitude for his conduct toward our people in the vicinity of Vicksburg. His considerate and kind treatment of them stood in bright contrast to the course pursued by many Federal officers."

Sherman in his official report of the death of McPherson, said in part: The country generally will realize that we have lost not only an able military leader, but a man who had he survived, was qualified to heal the national strife which has been raised by designing and ambitious men."