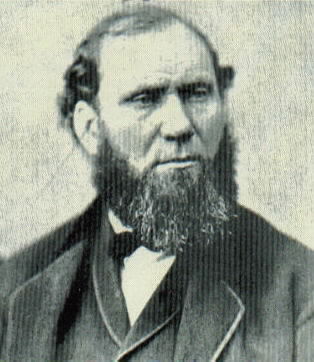

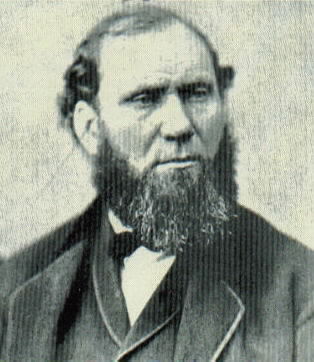

Allan Pinkerton (1819-1884)

Allan Pinkerton, detective, was born in Glasgow, Scotland, on August 25, 1819 and died in Chicago, Illinois, July 1, 1884. He the son of a Glasgow, Scotland, police sergeant, and learned the trade of barrel making in his native country. He became a Chartist in early manhood, came to this country in 1842 at the age of 23 to escape imprisonment. He settled in Chicago, Illinois, and set up his own cooperage in the town of Dundee near Chicago. One day, while cutting wood on a deserted river island, Pinkerton discovered the hideout of a gang of counterfeiters. He organized a group of citizens to lead back to the island and captured the counterfeiters, gaining a reputation that led to his being named a deputy sheriff of Kane county in 1846. He was subsequently deputy sheriff of Cook county, and in 1850 was appointed the first detective for Chicago. He also established Pinkerton's detective agency in that year, and from that date till the emancipation was largely engaged in assisting the escape of slaves.

In 1850, at the urging of railroad presidents, Pinkerton opened a private detective agency specializing in railroad security. He brought many innovations to the field of law enforcement and had a flourishing business. One of his railroad clients, the Illinois Central, also employed Abraham Lincoln for legal services and George B. McClellan as chief engineer.

He was the first special U S. mail agent for northern Illinois and Indiana and southern Wisconsin, organized the U. S. Secret Service division of the National Army in 1861, was its first chief, and subsequently organized and was at the head of the Secret Service Department of the Gulf till the close of the civil war. He added to his detective agency in Chicago in 1860 a corps of night-watchmen, called Pinkerton's Preventive Watch, established offices of both agencies in several other cities, and was extremely successful in the discovery and suppression of crime.

As the war approached, another of his clients, The Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad, became concerned that secessionists in Maryland would cut its tracks in order to isolate the nation's capital from the North. The railroad sent Pinkerton to Baltimore to protect its property. Pinkerton found Baltimore a hotbed of Southern sentiment and had some of his operatives infiltrate the secessionist groups in the city.

The agents learned of much more than Pinkerton had expected, including a plot to assassinate Lincoln when he passed through Baltimore on his way to Washington and his inauguration. Pinkerton and the railroad president, Samuel Felton, met with Lincoln, who had already begun the trip to Washington, in his hotel room in Philadelphia. At 10:30 the next night, Lincoln, his volunteer bodyguard and friend Ward Hill Lamon, and Allan Pinkerton quietly slipped aboard the last car of the train to Baltimore, where they would change trains in the middle of the night for the final leg to Washington. After safely escorting President-elect Abraham LIncoln to Washington in February 1861, Allan Pinkerton was employed as chief of secret service by General George B. McClellan, then in the Department of the Ohio. When McClellan was chosen as commander of the Army of the Potomac, Pinkerton went with him to Washington, and then to Virginia to conduct spying operations for McClellan's Peninsular campaign. Pinkerton and his 16 or so male and female spies, who were operatives from his detective agency induced to accompany him to war, were excellent detectives and did a good job of gathering pertinent information. They interrogated escaping slaves for information about Rebel troop strength and movements. In addition to conducting operations themselves behind enemy lines, Pinkerton's spies also recruited and educated reliable blacks as spies and sent them back for more information.

Pinkerton had a flaw, however, and it was a big one: he misinterpreted much of the information he gathered. The reports he supplied to McClellan, signed with the code name "Major E.J. Allen", consistently inflated the number of enemy troops. While the Confederates could scarcely put 80,000 men in the field against McClellan, Pinkerton reported and enemy strength of 200,000. This erroneous information, coupled with his natural cautiousness, caused McClellan to constantly call on Washington for more men and supplies, to fritter away opportunities to deliver devastating blows on his out numbered foe, and ultimately to lose the campaign.

Pinkerton accompanied McClellan to Sharpsburg, where he contributed little to the Maryland campaign. When McClellan was removed from command in November 1862, Pinkerton resigned his position as head of the secret service and returned to his lucrative Chicago detective agency. His only military work until the end of the war was to investigate fraud by government contractors supplying war materials.

Among the cases in which he successfully traced thieves and recovered money are the robbery of the Carbondale, Pennsylvania Bank of $40,000, and that of The Adams Express Company of $700,000, on 6 January, 1866, from a train on The New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad, and the taking of $300,000 from an express-car on the Hudson River railroad. He also broke up gangs of thieves at Seymour, Indiana, and the "Mollie Maguires" in Pennsylvania. He published about fifteen detective stories, the most popular of which are "The Molly Maguires and the Detectives" (New York, 1877) ; "Criminal Reminiscences" (1878); "The Spy of the Rebellion" (1883); and "Thirty Years a Detective" (1884).