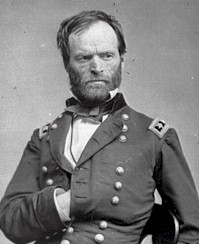

William Tecumseh Sherman (1820-1897)

William Tecumseh Sherman (February 8, 1820 - February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, and author. He served as a general in the United States Army during the American Civil War (1861-1865), achieving both recognition for his outstanding command of military strategy, particularly his mastery and perfection of the indirect approach, and criticism for the harshness of the "scorched earth" policies he implemented in dealing with the enemy. British military historian Liddell Hart famously declared that Sherman was "the first modern general."

Early life

Sherman was born in Lancaster, Ohio, on February 8, 1820. He was named Tecumseh, after the famous chief of the Shawnee tribe who Sherman's Grandfather had fought while serving under General (and later President) William Henry Harrison at the Battle of Tippecanoe. Sherman was one of eight children of Judge Charles R. Sherman, who died when the boy was only nine. His younger brother John Sherman would later become a U.S. Senator and the sponsor of the Sherman Antitrust Act. Following the death of his father, Tecumseh Sherman was taken in and raised by a Lancaster neighbor and family friend, attorney Thomas Ewing, a prominent member of the Whig Party who served as a Senator from Ohio and as U.S. Secretary of the Interior. The name of William was bestowed upon him at this time when Ewing's wife, Maria, insisted Sherman be baptized Roman Catholic. Sherman never truly accepted "William" however and friends and family always called him "Cump".

Ewing secured the appointment of the 16 year old Sherman as a cadet in the United States Military Academy at West Point, from which he graduated sixth in his class of 1840. After graduation entered the army as a second lieutenant and was sent to fight Seminole Indians in Florida and was eventually transferred to Fort Moultrie, South Carolina. The Mexican War, in which so many future generals of the Civil War received their experience, passed Sherman by; he was stranded in California as an administrative officer.

In 1850 he married Eleanor Boyle Ewing, daughter of his adoptive father Thomas Ewing, who was then serving as secretary of the interior in Washington. They settled in St. Louis, Missouri. Three years later he resigned his military commission and join a St. Louis banking firm as president at its branch in San Francisco. Sherman's arrival in San Francisco was indicative of the turmoil of his time in the West: he survived not one but two shipwrecks and floated through the Golden Gate on the scraps of a foundering lumber schooner. Sherman eventually found himself suffering from stress-related asthma thanks to the city's brutal financial climate. Late in life, regarding his time in real estate speculation-mad San Francisco, Sherman recalled: "I can handle a hundred thousand men in battle, and take the City of the Sun, but am afraid to manage a lot in the swamp of San Francisco."

Sherman's bank failed during the financial panic of 1857 and he was forced to accept a job in January 1860 as the first president of the Louisiana State Seminary and Military Academy at Alexandria (after the war, the school moved to Baton Rouge, Louisiana and became Louisiana State University). The position had been offered to him by two of his Southern army friends: P.G.T. Beauregard and Braxton Bragg. Ironically, the first president of what is now one of the most prestigious and beloved Southern universities was a Yankee general who would later be remembered as one of the most hated men in the South. Talk of the secession from the Union was now rampant, yet the motto of the seminary was "By the liberality of the General Government of the United States, the Union - esto perpetua." When Louisiana seceded from the Union in January 1861, Sherman resigned his post on January 18, 1861, stating that he preferred to maintain his allegiance to the Constitution as long as a fragment of it survived. On February 25, Sherman left Louisiana and returned to Ohio. He remained in Lancaster for a month and then moved his family to St. Louis, Missouri where he was elected President of the Fifth Street Railroad in April 1861. He held the position for less than two months before being called to Washington, using the influence of his younger brother, Senator John Sherman, to obtain an appointment in the U.S. Army as a colonel in May 1861.

Reaction to secession

On hearing of South Carolina's secession, Sherman presciently observed to a southern friend before going north to serve in the Union Army: "You people of the South don't know what you are doing. This country will be drenched in blood, and God only knows how it will end. It is all folly, madness, a crime against civilization! You people speak so lightly of war; you don't know what you're talking about. War is a terrible thing! You mistake, too, the people of the North. They are a peaceable people but an earnest people, and they will fight, too. They are not going to let this country be destroyed without a mighty effort to save it. . . . Besides, where are your men and appliances of war to contend against them? The North can make a steam engine, locomotive, or railway car; hardly a yard of cloth or pair of shoes can you make. You are rushing into war with one of the most powerful, ingeniously mechanical, and determined people on Earth—right at your doors. You are bound to fail. Only in your spirit and determination are you prepared for war. In all else you are totally unprepared, with a bad cause to start with. At first you will make headway, but as your limited resources begin to fail, shut out from the markets of Europe as you will be, your cause will begin to wane. If your people will but stop and think, they must see in the end that you will surely fail."

Service to the Union

Beauregard and Bragg both became Confederate generals during the Civil War. Sherman accepted a commission as a colonel in the U.S. Army. His assignments included: colonel, 13th Infantry (May 14, 1861); commanding 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, Army of Northeastern Virginia June-August 17, 1861); brigadier general, USV (August 7, 186 1, to rank from May 17); commanding brigade, Division of the Potomac (August 17-28, 1861); second-in-command, Department of the Cumberland (August 28 - October 8, 1861); commanding the department (October 8 - November 9, 1861); commanding District of Cairo, Department of the Missouri (February 14 - March 1, 1862); commanding 5th Division, Army of the Tennessee (March 1 - July 21, 1862); major general, USV (May 1, 1862); commanding 5th Division, District of Memphis, Army of the Tennessee July 21 - September 24, 1862); commanding lst Division, District of Memphis, Army of the Tennessee (September 24-October 26, 1862); also commanding the district July 21 - October 26, 1862); commanding District of Memphis, 13th Corps, Army of the Tennessee (October 24 - November 25, 1862); commanding Yazoo Expedition, Army of the Tennessee (December 18, 1862 January 4, 1863); commanding 2nd Corps, Army of the Mississippi January 4-12, 1863); commanding 15th Corps, Army of the Tennessee January 12 - October 29, 1863); brigadier general, USA July 4, 1863); commanding Army and Department of the Tennessee (October 24, 1863 - March 26, 1864); commanding Military Division of the Mississippi (March 18, 1864 - June 27, 1865); major general, USA (August 12, 1864); lieutenant general, USA July 25, 1866); general, USA (March 4, 1869); and commander-in-chief, USA (March 8, 1869-November 1, 1883).

On May 8, 1861, Sherman wrote to the Secretary of War, offering his services not for three months, but for three years. He did not want to become a political general and on June 20, 1861 accepted the grade of Colonel in the 13th Regular Infantry. He assumed command of a brigade in the 1st Division of McDowell's army under the command of Brigadier-General Daniel Tyler and fought in the disastrous first Battle of Bull Run (July 21, 1861). He was one of the few Union officers to distinguish themselves at that battle, leading the brigade of volunteers of the 1st Division which crossed Bull Run to aid the 2nd and 3rd divisions after the attack on the enemy left had begun. But the disastrous Union defeat led Sherman to question his own judgment as an officer and to request that President Abraham Lincoln relieve him of independent command, which Lincoln refused to do, promoting him instead to Brigadier General. Briefly commanding a brigade around Washington, he was then sent to Kentucky as deputy to Robert Anderson. He soon succeeded the hero of Fort Sumter in command of the department.

In October 1861 Sherman succeeded to the command in Kentucky. Filling quotas for Kentucky volunteers was extremely difficult. The State was split on their beliefs and where their allegiance should be placed. Later that month, Sherman told Secretary of War Cameron that if he had 60,000 men, he would drive the enemy out of Kentucky, and if he had 200,000 men, he would finish the war in that section. When Cameron returned to Washington, he reported that Sherman required 200,000 men. The report was given to newspapers and a cry of indignation arose from the public. A writer of one of these newspapers even went as far as saying that Sherman must be "crazy" in demanding such a large force. The public accepted this insinuated statement as a valid one, thus writers have always declared that he was crazy. Due to the pressure of the press and politicians that believed the insinuation, on November 12, 1861, Brigadier-General Don Carlos Buell relieved Sherman of his command, and Sherman was assigned to the Department of the West, in St. Louis, Missouri under Major-General Halleck. After moving to Missouri, newspapers and gossip continued to harass him with reports that he was insane and that he was not fit to command, demanding his recall. He was in a state of depression from all the harassment, but not mentally incompetent. Halleck, in a letter to Sherman's foster father stated, "I have seen newspaper squibs charging him with being "crazy", etc. This is the grossest injustice. I do not however, consider such attacks worthy of notice." But again, while inspecting troops in the central part of the state, Sherman allowed his overactive imagination to run away with him. During the campaign against Forts Henry and Donelson he was stationed at Paducah, Kentucky and charged with forwarding reinforcements to Grant. Forming a good working relationship with the future commander-in-chief, Sherman offered to waive his seniority rights and take a command under him.

He quickly returned to the service and just six months later performed brilliantly and bravely as Major General under the command of Ulysses S. Grant at the Battle of Shiloh (April 6-7, 1862). Commanding a division, he was largely responsible for the poor state of preparedness at Shiloh but redeemed himself during the defensive fighting of the first day and was wounded. He suffered two slight wounds during the battle and had four horses shot from under him. The next day his command played only a minor role. Praised by Grant, he was soon made a major general of volunteers.

Grant had a calming influence upon Sherman. Sherman developed close personal ties to Grant during the two years they served together. In later years Sherman said simply, "Grant stood by me when I was crazy, and I stood by him when he was drunk. Now we stand by each other always." At one point, not long after the Battle of Shiloh, Sherman persuaded Grant not to resign from the army, despite the serious difficulties he was having with his commander, General H. W. Halleck, during the advance on Corinth, Mississippi. Together they fought brilliantly to capture Vicksburg, Mississippi (1862-63), shattering the Confederate defenses and opening the Mississippi River to Northern commerce once more. During the early operations against Vicksburg Sherman ordered a doomed assault at Chickasaw Bluffs and a few days later was superseded by John A. McCiernand who accepted Sherman's proposal to attack Arkansas Post. Grant initially criticized this movement as unnecessary but declared it an important achievement when it succeeded and he learned that Sherman had suggested it. Sherman's corps did little fighting in the advance on Vicksburg in May until the disastrous assaults were made.

Sherman's star, along with Grant's, was now in the ascendant, and their careers were thenceforth closely linked as they worked together to bring about a Union victory in the war. Following the fall of Vicksburg, Sherman was named a brigadier general in the regular army and led an expedition against Jackson. That fall he went to the relief of Chattanooga where he failed to achieve his objectives in the assault against Tunnel Hill at the end of Missionary Ridge. Nonetheless, he was highly praised by Grant who then sent him to relieve the pressure on Burnside at Knoxville. Back in Mississippi, he led the Meridian expedition. When Grant was placed in supreme command in the west, Sherman succeeded to the command of the Army of the Tennessee and in that capacity took part with Grant in the Chattanooga campaign in November 1863.

When Lincoln called Grant east in the March 1864 to take command of all Union armies, Grant appointed Sherman his successor commander of the military division of the Mississippi, with three armies under his overall command.

Assembling about 100,000 troops near Chattanooga, Tennessee, in May 1864, he began his invasion of Georgia. Facing Joseph E. Johnston's army, he forced it all the way back to Atlanta where the Confederate was replaced by John B. Hood who launched three disastrous attacks against the Union troops near the city. Eventually taking possession of Atlanta, a vital industrial centre and the hub of the Southern railway network, on September 2, 1864, Sherman ordered the population evacuated and the military value of the city destroyed. Sherman's capture of Atlanta was a much-needed victory that restored Northern morale and helped ensure Lincoln's reelection that November. Sending George H. Thomas back to Middle Tennessee to deal with Hood, he embarked on his March to the Sea.

Sherman's siege and capture of Atlanta, Georgia and the subsequent March to the Sea from Atlanta to Savannah from November 15 to December 21, 1864 sealed Sherman's position as one of the leading Union generals of the Civil War. Union superiority in manpower was now having its effect, and Sherman was able to detach part of his army and lead the remaining 62,000 troops on the celebrated "March to the Sea" from Atlanta to Savannah on the Atlantic coast. Separated from its supply bases and completely isolated from other Union forces, Sherman's army cut a wide swath as it moved south through Georgia, living off the countryside, destroying railroads and supplies, reducing the war-making potential of the Confederacy, and bringing the war home to the Southern people. Sherman reached Savannah in time for Christmas and "presented" the city to Lincoln with 150 captured cannons and 25,000 bales of cotton. By February 1865 he was heading north through the Carolinas toward Virginia, where Grant and the Confederate commander General Robert E. Lee were having a final showdown. The opposing Confederate forces led by Johnston could offer Sherman only token resistance by now. He drove through the Carolinas and accepted Johnston's surrender at Durham Station. His terms were considered too liberal and touching upon political matters and they were disapproved by Secretary of War Stanton. This led to a long-running feud between the two. Lee surrendered to Grant in Virginia on April 9, and Johnston surrendered the remnants of his forces to Sherman on April 26 near Durham, North Carolina, on the basis of the Appomattox surrender.

Sherman remained a soldier to the end, though his view of warfare was succinctly put in his oft-quoted assertion that "war is hell." Convinced that the Confederacy's ability to wage further war had to be definitively crushed if the fighting was to end (and that, therefore, the North had to approach the ongoing conflict as a war of conquest), Sherman's advance through Georgia and the Carolinas was sometimes accompanied by looting (though officially forbidden, there is controversy as to how well enforced this position was) and always by widespread destruction of civilian supplies and infrastructure. This was, indeed, the point. To destroy the will and ability of the South to make war while limiting human casualties on all sides. The targetting of civilians and accusations of war crimes on the march have made Sherman a controversial figure, particularly in the American South, to this day. Many Southerners called him a controversial figure for ransacking their homes, while slaves called him a liberator for freeing them. In reality, both of these claims do not tell the whole truth. The damage done by Sherman was almost entirely limited to property destruction—particularly property that could aid the Confederate war effort. The loss of life (especially civilian life) was remarkably minimal, especially when considering the size of his two-pronged army advance through the area (60,000 plus troops, in an advance that was 60 miles wide and 300 miles long). This was always Sherman's goal and several of his southern contemporaries noted this fact and commented on it. On the slave issue as well, the situation is not so black and white. Sherman was more than a little duplicitous when it came to his views and treatment of Blacks. Chattle slavery was not something he approved of, and his actions did free many a slave from bondage, but he was, like many in his time, not a believer in "Negro equality".

Sherman was the only man to twice receive the Thanks of Congress during the Civil War—first for Chattanooga and second for Atlanta and Savannah.

After the Civil War

When Grant became a full general in 1866, Sherman moved up to the rank of lieutenant general. Sherman was appointed commander of the Missouri district, which stretched from the Rocky Mountains to the Mississippi. Here he deployed troops to protect transcontinental railroad workers from Indians who feared that the railroad would mean further encroachment on their territory. He also established military outposts across the region, expanding the network of federal authority. In these years, Sherman was outspoken in his belief that Indian policy should be set by the army, and that the aim of Indian policy should be to place the various tribes on reservations and force them to stay there. He once declared that all Indians not on reservations "are hostile and will remain so until killed off." As a member of the peace commission that negotiated the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867 and the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, he was partly able to put his beliefs into practice, influencing the assignment of tribes each to its own separate and limited territory

When Grant became president in 1869, he made Sherman commanding general of the army, a post he held until his retirement in 1884. One of his most important contributions after the war, was the establishment of the Command School at Ft. Leavenworth. As command general, Sherman directed various campaigns against the Indian tribes. As in his Civil War service, in these campaigns Sherman sought not only to defeat the enemy's soldiers, but also to destroy the resources that allowed the enemy to sustain its warfare, finally crushing Indian resistance across the plains. He perceived clearly the devastating effectiveness of striking at the economic basis of the Plains Indians' lives, once commenting to General Philip Sheridan that "it would be wise to invite all the sportsmen of England and America . . . for a Grand Buffalo Hunt, and make one grand sweep of them all." And he endorsed Sheridan's innovation of attacking Indian encampments during the winter, when their supplies and mobility were both severely limited. With Sheridan as his field commander, Sherman moved first against the Kiowas and Comanches of the southern Plains, then against the Lakota and Cheyenne of the north. By the late 1870s, these and the other once free-roaming warrior tribes of the plains had been forced onto reservations. Despite his harsh treatment of the warring Indian tribes, Sherman spoke out against government agents who treated the natives unfairly within the reservations.

In 1875 Sherman published his two-volume memoirs, a minor classic, marked by a forceful, lucid style, and the strong opinions for which Sherman has become famous. Sherman retired from the army in 1884, and lived most of the rest of his life in New York City. He was devoted to the theatre and was much in demand as a colorful speaker at dinners and banquets.

Unlike Grant, Sherman declined all opportunities to run for political office. He was proposed by some Democrats as a possible presidential candidate for the election of 1884. He declined as emphatically as possible, saying, "If nominated I will not run; if elected I will not serve." Such a categorical rejection of a candidacy is now referred to as a "Sherman Statement."

Death

In 1886 Sherman made his home in New York City, where he died on February 14, 1891, and is memorialized by an equestrian statue created by Augustus Saint-Gaudens and located the southeast entrance to Central Park. He is buried in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri.

General Joseph E. Johnston, the Confederate officer who had commanded the resistance to Sherman's troops as they marched through Georgia and South Carolina, served as a pallbearer at Sherman's funeral. It was a bitterly cold day in February, and a friend of Johnston, fearing that the general might become ill, asked him to put on his hat. Johnston famously replied: "If I were in [Sherman's] place, and he were standing in mine, he would not put on his hat." Johnston did catch a serious cold, and died soon afterwards.