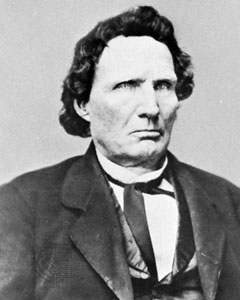

Thaddeus Stevens (1792-1868)

U.S. Radical Republican congressional leader during Reconstruction (1865-77) who battled for freedmen's rights and insisted on stern requirements for readmission of Southern states into the Union after the Civil War (1861-65).

Admitted to the Maryland bar, he moved to Pennsylvania to practice law in 1816. Having witnessed the oppressive slave system at close range, he early developed a fierce hatred of bondage and defended numbers of fugitives without fee. An anti-Masonic member of the state legislature (1833-41), he proved himself a friend of banks, internal improvements, and public schools and a foe of Freemasons, Jacksonian Democrats, and slaveholders. Serving as a Whig in the U.S. House of Representatives (1849-53), he advocated tariff increases and opposed the fugitive slave provision of the Compromise of 1850.

Admitted to the Maryland bar, he moved to Pennsylvania to practice law in 1816. Having witnessed the oppressive slave system at close range, he early developed a fierce hatred of bondage and defended numbers of fugitives without fee. An anti-Masonic member of the state legislature (1833-41), he proved himself a friend of banks, internal improvements, and public schools and a foe of Freemasons, Jacksonian Democrats, and slaveholders. Serving as a Whig in the U.S. House of Representatives (1849-53), he advocated tariff increases and opposed the fugitive slave provision of the Compromise of 1850.

His reputation grew for his use of the insanity defense in a murder case, a novelty at the time. Eventually he acquired a great deal of land in the area and went into the iron business. Although one of his forges was a frequent money loser, he kept it going rather than displace his employees. In politics he moved from Federalist to Anti-Mason, to Whig, and finally to Republican. He served in the state legislature from 1833 until 1842, where he is most remembered for his defense of free public schools. He was a master at the distribution of patronage, especially on the unnecessary Gettysburg railroad. In 1842 he returned to the management of his personal affairs, including the donation of land to what is now Gettysburg College. Elected to Congress as a Whig in 1848, he was a constant opponent of extending slavery or appeasing the South in any way.

In the middle of the decade he joined the newly formed Republican Party, which opposed extension of slavery into the western territories; again he was elected to Congress (1859-68), where he became, in the words of a fellow member, the "natural leader, who assumed his place by common consent." He exerted this leadership by means of his sarcastic eloquence, his parliamentary skills, and his privileges as chairman of the Ways and Means Committee and later of the Appropriations Committee.

During the Civil War he wielded great influence as head of the House Ways and Means Committee. Although he had supported Lincoln in 1860, he was a constant critic of his moderate actions against the South, favoring instead a war of extermination and recolonization of the South, abolishing the old state lines. With his control of the Congress' purse, he became a leader of the Radical Republicans. The Confederates, however, got even with him for his harsh rhetoric by burning his Caledonia ironworks during the Gettysburg Campaign. Stevens provided for the support of some of the families, who were unemployed by this action, for as long as three years.

After the war Stevens emerged as one of the most militant of the Radical Republicans, consistently striving for justice for the black masses. Alert to the return to power of traditional white Southern leadership, he argued that the seceded states were in the condition of "conquered provinces" to which restraints of the Constitution did not apply.

When Congress met in December 1865, Stevens took the lead in excluding the traditional senators and representatives from the South. As a member of the joint Committee on Reconstruction, he played an important part in the preparation of the Fourteenth (due process) Amendment to the Constitution and the military reconstruction acts of 1867. Viewing Pres. Andrew Johnson as "soft" toward the South, he introduced the resolution for his impeachment (1868) and served as chairman of the committee appointed to draft impeachment articles. Throughout this period Stevens urged that Southern plantations be taken from their owners and that part of the land be divided among freedmen, with proceeds of the balance to be used toward paying off the national war debt; this confiscation plan failed, however, to gain congressional support.

In failing health, Stevens requested that he be buried among Negroes resting in a cemetery in Lancaster, Pa. On his tombstone were carved the words he had composed, explaining that he had chosen this place so that he might "illustrate in death" the principle he had "advocated throughout a long life"; namely, "Equality of man before his Creator." (Encyclopaedia Britannica)

Admitted to the Maryland bar, he moved to Pennsylvania to practice law in 1816. Having witnessed the oppressive slave system at close range, he early developed a fierce hatred of bondage and defended numbers of fugitives without fee. An anti-Masonic member of the state legislature (1833-41), he proved himself a friend of banks, internal improvements, and public schools and a foe of Freemasons, Jacksonian Democrats, and slaveholders. Serving as a Whig in the U.S. House of Representatives (1849-53), he advocated tariff increases and opposed the fugitive slave provision of the Compromise of 1850.

Admitted to the Maryland bar, he moved to Pennsylvania to practice law in 1816. Having witnessed the oppressive slave system at close range, he early developed a fierce hatred of bondage and defended numbers of fugitives without fee. An anti-Masonic member of the state legislature (1833-41), he proved himself a friend of banks, internal improvements, and public schools and a foe of Freemasons, Jacksonian Democrats, and slaveholders. Serving as a Whig in the U.S. House of Representatives (1849-53), he advocated tariff increases and opposed the fugitive slave provision of the Compromise of 1850.