The cultural legacy of ancient Athens to the world is incalculable; to a great extent the references to the Greek heritage that abound in the culture of Western Europe are to Athenian civilization. Athens, named after its patron goddess Athena, was inhabited in the Bronze Age. Its citizens later proudly claimed that their ancestors had lived in the city even before the settlements of Attica were molded into a single state (according to legend, by Theseus).Early History

According to tradition, Athens was governed until c.1000 B.C. by Ionian kings, who had gained suzerainty over all Attica. After the Ionian kings Athens was rigidly governed by its aristocrats through the archontate (see archons), until Solon began to enact liberal reforms in 594 B.C. Solon abolished serfdom, modified the harsh laws attributed to Draco (who had governed Athens c.621 B.C.), and altered the economy and constitution to give power to all the propertied classes, thus establishing a limited democracy. His economic reforms were largely retained when Athens came under (560511 B.C.) the rule of the tyrant Pisistratus and his sons Hippias and Hipparchus. During this period the city's economy boomed and its culture flourished. Building on the system of Solon, Cleisthenes then established (c.506 B.C.) a democracy for the freemen of Athens, and the city remained a democracy during most of the years of its greatness.

A Great City-State

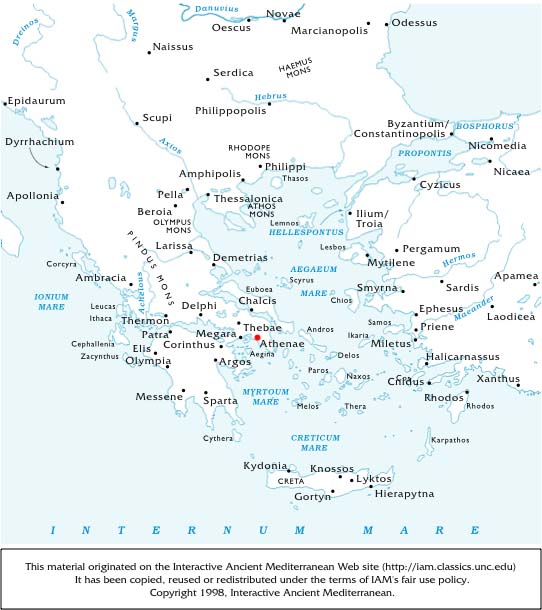

The Persian Wars (500449 B.C.) made Athens the strongest Greek city-state. Much smaller and less powerful than Sparta at the start of the wars, Athens was more active and more effective in the fighting against Persia. The Athenian heroes Miltiades, Themistocles, and Cimon were largely responsible for building the city's strength. In 490 B.C. the Greek army defeated Persia at Marathon. A great Athenian fleet won a major victory over the Persians off the island of Salamis (480 B.C.). The powerful fleet also enabled Athens to gain hegemony in the Delian League, which was created in 478477 B.C. through the confederation of many city-states; in succeeding years the league was transformed into an empire headed by Athens. The city arranged peace with Persia in 449 B.C. and with its chief rival, Sparta, in 445 B.C., but warfare with smaller Greek cities continued.

During the time of Pericles (443429 B.C.) Athens reached the height of its cultural and imperial achievement; Socrates and the dramatists Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides were active. The incomparable Parthenon was built, and sculpture and painting flourished. Athens became a center of intellectual life. However, the rivalry with Sparta had not ended, and in 431 B.C. the Peloponnesian War between Sparta and Athens began. The war went badly for Athens from the start. The Long Walls built to protect the city and its port of Piraiévs saved the city itself as long as the fleet was paramount, but the allies of Athens fell away and the land empire Pericles had tried to build already had crumbled before his death in 429 B.C. The war dragged on under the leadership of Cleon and continued even after the collapse of the expedition against Sicily, urged (415 B.C.) by Alcibiades. The Peloponnesian War finally ended in 404 B.C. with Athens completely humbled, its population cut in half, and its fleet reduced to a dozen ships. Under the dictates of Sparta, Athens was compelled to tear down the Long Walls and to accept the government of an oligarchy called the Thirty Tyrants. However, the city recovered rapidly. In 403 B.C. the Thirty Tyrants were overthrown by Thrasybulus, and by 376 B.C. Athens again had a fleet, had rebuilt the Long Walls, had re-created the Delian League, and had won a naval victory over Sparta. Sparta also lost power as a result of its defeat (371 B.C.) by Thebes at Leuctra; and, although Athens did not again achieve hegemony over Greece, it did have a short period of great prosperity and comfort.

The Decline of Athens

The growth of Macedon's power under Philip II heralded the demise of Athens as a major power. Despite the pleas by Demosthenes to the citizens of Athens to stand up against Macedon, Athens was decisively defeated by Philip at Chaeronea in 338 B.C. The city did not dare dispute the mastery of Philip's son and successor, Alexander the Great. After his death Athens revolted (323322 B.C.) against control by Macedon, but the revolt was quashed, and Athens lost its remaining dependencies and declined into a provincial city. Its last bid for greatness (266262 B.C.) was firmly suppressed by Antigonus II, king of Macedon.

Through the troubled times of the Peloponnesian War and the wars against Philip, Athenian achievements in philosophy, drama, and art had continued. Aristophanes wrote comedies, Plato taught at the Academy, Aristotle compiled an incredible store of information, and Thucydides wrote a great history of the Peloponnesian War. As the city's glory waned in the 3d cent. B.C., its earlier contributions were spread over the world in Hellenistic culture.

Athens became a minor ally of growing Rome, and a period of stagnation was broken only when the city unwisely chose to support Mithradates VI of Pontus against Rome. As a result, Athens was sacked by the Roman general Sulla in 86 B.C. Nevertheless, Athens sent out many teachers to Rome and retained a certain faded glory as a moderately prosperous small city in the backwash of the empire. It remained so until the time when the Eastern Empire began to fall to the barbarians. Athens was captured in A.D. 395 by the Visigoths under Alaric I.

From Byzantine to Ottoman Rule

Athens became a provincial capital of the Byzantine Empire and a center of religious learning and devotion. Following the creation (1204) of the Latin Empire of Constantinople (see Constantinople, Latin Empire of), Athens passed (1205) to Othon de la Roche, a French nobleman from Franche-Comté, who was made megaskyr [great lord] of Athens and Thebes. His nephew and successor, Guy I, obtained the ducal title, and the duchy of Athens, under Guy I and his successors, enjoyed great prosperity while becoming thoroughly French in its institutions. In 1311 the duchy was captured by a band of Catalan soldier-adventurers who offered (1312) the ducal title to King Frederick II of Sicily, a member of the house of Aragón. Members of the house of Aragón carried the title, but Athens was in fact governed by the "Catalan Grand Company," which also acquired (1318) the neighboring duchy of Neopatras.

The French feudal culture disappeared, and Athens sank into insignificance and poverty, particularly after 1377, when the succession was contested in civil war. Peter IV of Aragón assumed sovereignty in 1381 but ruled from Barcelona. On his initiative, the devastated duchy was settled by Albanians. Athens again prospered briefly after its conquest in 1388 by Nerio I Acciajuoli, lord of Corinth, a Florentine noble. Under the Acciajuoli family's rule numerous Florentine merchants established themselves in Athens. However, the fall of the Acropolis to the Ottoman Turks in 1458 marked the beginning of nearly four centuries of Ottoman rule, and Athens once more declined. Venice, which had held Athens from 1394 to 1402, recovered it briefly from the Turks in 1466 and besieged it in 168788. During the siege the Parthenon, used by the Turks as a powder magazine, was largely blown up in a bombardment.

Modern Athens

Modern Athens was constructed only after 1834, when it became the capital of a newly independent Greece. Otto I, first king of the Hellenes (183262), rebuilt much of the city, and the first modern Olympic games were held there in 1896. The population grew rapidly in the 1920s, when Greek refugees arrived from Turkey. The city's inhabitants suffered extreme hardships during the German occupation (194144) in World War II, but the city escaped damage in the war and in the country's civil troubles of 194450.

The 1950s and 60s brought unbridled expansion. Land clearance for suburban building caused runoff and flooding, requiring the modernization of the sewer system. The Mornos River was dammed and a pipeline over 100 mi (160 km) long was built to Athens, supplementing the inadequate water supply. The development of a highway system facilitated the proliferation of automobiles, resulting in increased air pollution. This accelerated the deterioration of ancient buildings and monuments, requiring preservation and conservation programs as well as traffic bans in parts of the city. The Ellinikon airport was modernized and enlarged to accommodate increased tourism. A strong earthquake jolted the city in 1999. (The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001)