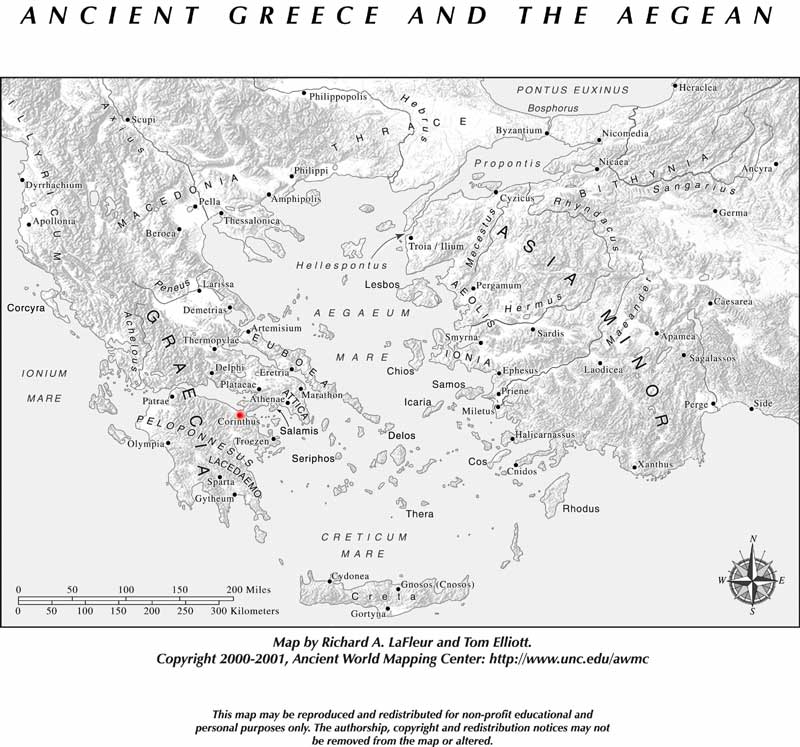

A famous city of Greece, situated on the isthmus of the same name. Commanding by its position the Ionian and the Aegean seas, and holding, as it were, the keys of the Peloponnesus, Corinth, from the pre-eminent advantages of its situation, was already the seat of opulence and the arts, while the rest of Greece was sunk in comparative obscurity and barbarism. Its origin is, of course, obscure; but we are assured that it already existed under the name of Ephurê before the siege of Troy. According to the assertions of the Corinthians themselves, their city received its name from Corinthus, the son of Zeus; but Pausanias does not credit this popular tradition, and cites the poet Eumelus to show that the appellation was really derived from Corinthus, the son of Marathon (ii. 1). Homer certainly employs both names indiscriminately ( Il.ii. 570; xiii. 663). Pausanias reports that the descendants of Sisyphus reigned at Corinth until the invasion of their territory by the Dorians and the Heraclidae, when Doridas and Hyanthidas, the last princes of this race, abdicated the crown in favour of Aletes, a descendant of Heracles, whose lineal successors remained in possession of the throne of Corinth during five generations, when the crown passed into the family of the Bacchiadae, so named from Bacchis, the son of Prumnis, who retained it for five other generations. After this the sovereign power was transferred to annual magistrates, still chosen, however, from the line of the Bacchiadae, with the title of prutaneis.The oligarchy so long established by this rich and powerful family was at length overthrown, about B.C. 629, by Cypselus, who banished many of the Corinthians, depriving others of their possessions, and putting others to death ( Herod.v. 92). Among those who fled from his persecution was Demaratus, of the family of the Bacchiadae, who settled at Tarquinii in Etruria, and whose descendants became sovereigns of Rome. The reign of Cypselus was prosperous, and the system of colonization, which had previously succeeded so well in the settlements of Corcyra and Syracuse, was actively pursued by that prince, who added Ambracia, Anactorium, and Leucas to the maritime dependencies of the Corinthians.

Cypselus was succeeded by his son Periander. On the death of this latter (B.C. 585), after a reign of forty-four years, according to Aristotle, his nephew Psammetichus came to the throne, but lived only [p. 412] three years. At his decease Corinth regained its independence, when a moderate aristocracy was established, under which the Republic enjoyed a state of tranquillity and prosperity unequalled by any other city of Greece. We are told by Thucydides that the Corinthians were the first to build war-galleys or triremes; and the earliest naval engagement, according to the same historian, was fought by their fleet and that of the Corcyreans, who had been alienated from their mother-State by the cruelty and impolicy of Periander. The city is believed to have had at this time a population of 300,000 souls.

The arts of painting and sculpture, more especially that of casting in bronze, attained to the highest perfection at Corinth, and rendered this city the ornament of Greece, until it was stripped by the rapacity of a Roman general. Such was the beauty of its vases, that the tombs in which they had been deposited were ransacked by the Roman colonists whom Iulius Caesar had established there after the destruction of the city; and these, being transported to Rome, were purchased at enormous prices. See Aes.

When the Achaean League (q.v.) became involved in a destructive war with the Romans, Corinth was the last hold of their tottering Republic; and had its citizens wisely submitted to the offers proposed by the victorious Metellus, it might have been preserved; but the deputation of that general having been treated with scorn and even insult, the city became exposed to all the vengeance of the Romans (Polyb. xl. 4. 1). L. Mummius, the consul, appeared before its walls with a numerous army, and after defeating the Achaeans in a general engagement, entered the town, now left without defence and deserted by the greater part of the inhabitants. It was then given up to plunder and finally set on fire; the walls also were razed to the ground, so that scarcely a vestige of this once great and noble city remained (B.C. 146). Polybius, who saw its destruction, affirmed that he had seen the finest paintings strewed on the ground, and the Roman soldiers using them as boards for dice or draughts. Pausanias reports (vii. 16) that all the men were put to the sword, the women and children sold, and the most valuable statues and paintings removed to Rome. (See Mummius.) Strabo observes that the finest works of art which adorned that capital in his time had come from Corinth. He likewise states that Corinth remained for many years deserted and in ruins. Iulius Caesar, however, not long before his death, sent a numerous colony thither, by means of which Corinth was once more raised from its state of ruin, and renamed Colonia Iulia Corinthus. It was already a large and populous city and the capital of Achaia, when St. Paul preached the Gospel there for a year and six months (Acts, xviii. 11). It is also evident that when visited by Pausanias it was thickly adorned by public buildings and enriched with numerous works of art, and as late as the time of Hierocles we find it styled the metropolis of Greece. In a later age the Venetians received the place from a Greek emperor; Mohammed II. took it from them in 1458; the Venetians recovered it in 1699, and fortified the Acrocorinthus again; but the Turks took it anew in 1715, and retained it until driven from the Peloponnesus in 1822. In 1858, it was wholly destroyed by an earthquake, since which time it has been rebuilt upon a site three miles to the northeast. [p. 413]

An important feature of the scenery around Corinth was the Acrocorinthus, a mention of which has been made in a previous article. (See Acrocorinthus.) On the summit of this hill was erected a temple of Aphrodité, to whom the whole of the Acrocorinthus, in fact, was sacred. In the times of Corinthian opulence and prosperity, it is said that the shrine of the goddess was attended by no less than one thousand female slaves, dedicated to her service as courtesans. These priestesses of Aphrodité contributed not a little to the wealth and luxury of the city, whence arose the well-known expression, ou pantos andros eis Korinthon est ho plous, or, as Horace expresses it (Epist. i. 17, 36), "Non cuivis homini contingit adire Corinthum," in allusion to its expensive pleasures.

Corinth was famed for its three harbours--Lechaeum, on the Corinthian Gulf, and Cenchreae and Schoenus, on the Saronic. Near this last was the Diolkos, where vessels were transported over the isthmus by machinery. The city was the birthplace of the painters Ardices, Cleophantus, and Cleanthes; of the statesmen Periander, Phidon, Philolaüs, and Timoleon; and of Arion , who invented the dithyramb.

See Wagner, Rerum Corinthiacarum Specimen (Darmstadt, 1824); Barth, Corinthiorum Commercii et Mercaturae Historiae Particula (Berlin, 1844); and E. Curtius, Peloponnesos, vol. ii. p. 514 foll. (Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1898)