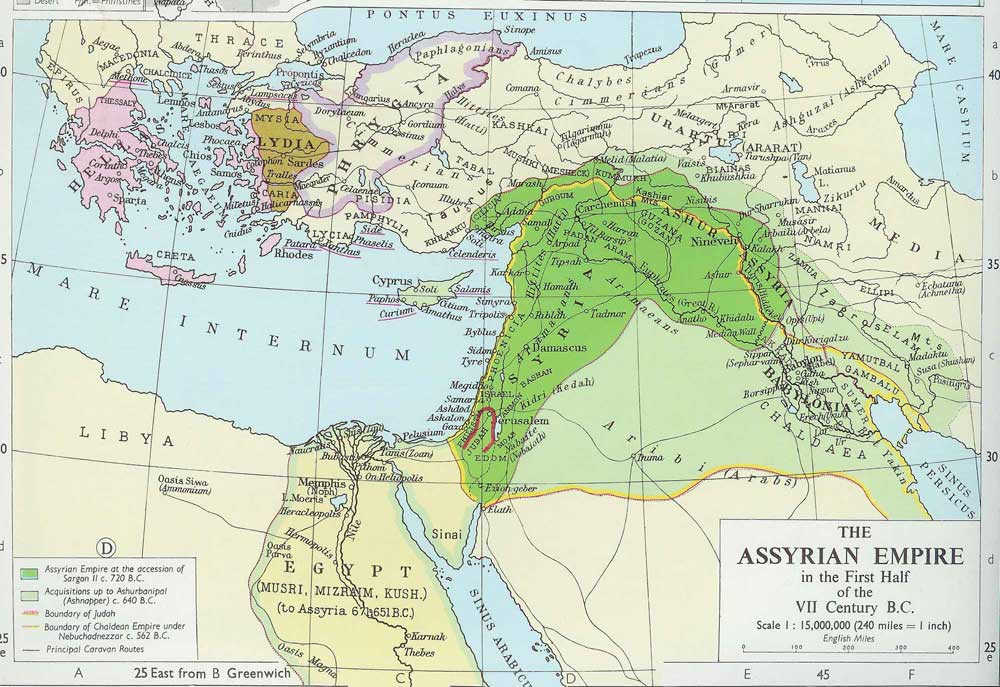

The country properly so called, in the narrowest sense, was a district of Asia, extending along the east side of the Tigris, which divided it on the west and northwest from Mesopotamia and Babylonia, and bounded on the north and east by Mount Niphates and Mount Zagrus, which separated it from Armenia and Media, and on the southeast by Susiana. It was watered by several streams flowing into the Tigris from the east, two of which, the Lycus or Zabatus (Great Zab) and the Caprus or Zabas (Little Zab), divided the country into three parts. The district between the upper Tigris and the Lycus , called Atturia, was probably the most ancient seat of the monarchy, containing the capital, Nineveh or Ninus. The Lycus and the Little Zab bounded the finest portion, called Adiabené. The district southeast of the Little Zab contained the two subdivisions Apolloniatis and Sittacené. In a wider sense the name Assyria was used to designate the whole country watered by the Tigris and Euphrates, including Mesopotamia and Babylonia; and in a still more extended application it meant the whole Assyrian Empire, one of the first great states of which we have any record.The remarkable fertility of the country enabled it to support a large population; and its great material prosperity, power, and culture are attested [p. 143] by ancient writers, as well as by the monuments that remain to us in the shape of ruins of cities, extensive canals and water-works, and proofs secured by excavators of the possession of the arts and sciences. At the present day the country is almost a desert; but from Tekrit to Bagdad, and in the vicinity of Nineveh (q.v.), abundant ruins mark the former wealth and splendour of the people.

Ethnology. The Assyrians were a branch of the Semitic race, to which the Syrians, Ph¦nicians, Jews, and Arabs belonged, and which in Chaldaea appears to have supplanted the Scythic or Turanian stock as early as B.C. 2100. Assyria had in the earliest times a close connection with Aethiopia and Arabia. Hence Herodotus speaks of Sennacherib as king of the Arabians as well as of the Assyrians. See Babylonia.

Language. The language of the Assyrians is allied to the North Branch of the Semitic family, its vocabulary showing a close affinity to Hebrew and Ph¦nician. In the fulness of its verbal system and richness of synonyms, however, it resembles the Arabic. The ethnic type of the Assyrians is the Semitic modified by some admixture with Akkadian elements. See Akkad; Cuneiform Inscriptions.

Assyrian literature is known to us chiefly from the discovery in the palace of Assur-bani-pal, at Nineveh, of a library of many thousand tablets collected by that king and his father, Esar-haddon. Duplicate copies of some of these tablets have been found in excavating the Babylonian cities. Of these tablets, many are syllabaries, dictionaries, geographies, and other educational works, often couched in the ancient Akkadian and Sumirian tougues; so that from them, Assyriologists have learned much about the older languages of Chaldaea. The richest literary discoveries, however, have been in the field of poetry and mythology. In 1872 the late Mr. George Smith, of the British Museum, discovered a series of tablets containing an epic in twelve books, one of which relates to the legend of the Deluge, and bears a very striking resemblance to the account given in the Old Testament. In both accounts the Deluge is a punishment for human sins; in both, the builder of an ark gathers into it his family and the beasts of the field; in both, the ark rests upon a mountain; in both, peace between God and man is restored; and in both, a sign of the restoration is the appearance of the rainbow. Many other interesting resemblances to portions of the Book of Genesis are contained in the Assyrian tablets. The hymns and prayers are likewise beautiful and poetic.

Results of Excavations. Successful excavations have been made by Botta, Layard, Oppert, Rawlinson, Smith, and others, with the result of opening up very many palaces and temples, and bringing to light sculptures covered with inscriptions, and including obelisks, sphinxes, winged lions and bulls, and bas-reliefs of battle-scenes, sieges, hunts, etc. Many smaller objects are no less interesting, such as ornaments, bells, engraved gems, and bronzes. It has been learned that the Assyrians were acquainted with glass; that they employed the arch in building; that they used the lens as a magnifying instrument; and had, among other mechanical appliances, the lever and the roller.

Religion. The religion of Assyria was simpler than that of the Babylonians, although polytheistic in character. The national deity was Assur, regarded as the founder [p. 144] of the nation. Beside him there are two principal triads, with many minor deities. The first triad is known as the Nature Triad (Ann "the Progenitor," Bel "the Lord of the World," Hea "the Lord of the Sea, Rivers, and Fountains"). The second triad is the Celestial Triad (Sin the Moon-god, Shamas the Sun-god, Istar the Stargoddess). Minor gods are Merodach or Marduk, son of Hea; Nebo the god of learning, who possesses many of the attributes of the Greek Hermes (q.v.); and Nergal and Nusku the war-gods. (See 2 Kings, xvii. 30.)

History. Ancient accounts of Assyrian history are those of Berosus (q.v.), a Graeco-Chaldean priest, who wrote at Babylon, where he had access to the inscriptional records, about B.C. 268; of Herodotus; and of Ctesias of Cnidus, physician to the Persian king Artaxerxes Mnemon (B.C. 405). The narrative of Berosus has met with much confirmation from recent excavations and explorations. In the Bible narrative we are told that Nineveh was founded from Babylonia. "Out of that land [Babylonia] he [Nimrod] went forth into Assyria" (Gen. x. 11)--and this statement is fully confirmed by the results of recent explorations. The earliest inscriptions found on the bricks from Assur (Kileh-Shergat), the ancient capital, give to the first rulers of the land the Akkadian title of Patesi, or "high-priest of the city of Assur," and to the city itself the Akkadian name of Pal-bi-ki. The next notice of Assyria does not occur until the Assyrian king Pul, or Tiglath-pileser II., invaded Palestine, and was bought off by Menahem, king of Israel (B.C. 738). In the same reign we find the Jewish king Jehoahaz (Ahaz) becoming a vassal of the court of Assyria, and the tribes beyond Jordan carried away captive (B.C. 734). In B.C. 722, Samaria is captured by Sargon the Tartan, who had usurped the throne from his weak master, Shalmaneser IV. The next reference to Assyria is that of the siege and capture of Jerusalem by Sargon (Isaiah, x., xi., xx.), and the siege of Ashdod (B.C. 712-711). This event is now proved to be distinct from the siege by Sennacherib in B.C. 701, which terminated apparently in a disaster for the Assyrian army. The last mention of Assyria is the record of the murder of Sennacherib by his sons in B.C. 681, and the accession of his faithful son Esar-haddon, the most powerful of all the Assyrian monarchs, for he carried his arms as far as the Mediterranean and conquered Egypt. Little credit is to be attached to the expedition of Holofernes recorded in the apocryphal Book of Judith.

After this the Empire appears to have gradually decayed, until at last, in the reign of Assur-banipal or Sardanapalus, or that of Esar-haddon II. (Sarakos), a league for its destruction was formed between Nabopolassar, governor of Babylon, and Cyaxares, king of Media, which was strengthened by the marriage of Nebuchadnezzar, son of the former, to Nitocris, daughter of the latter. The war and siege are said to have been interrupted by an invasion of the Scythians, which drew off Cyaxares; but at length Nineveh was taken and destroyed about B.C. 605, or, according to Rawlinson, 625. In the time of Darius Hystaspes Assyria rebelled without success in conjunction with Media. In the time of Herodotus the capital had ceased to exist; and when Xenophon passed it the very name was forgotten, though he testifies to the extent of the deserted city, and asserts the height of the ruined walls to be 150 feet. An inconsiderable town seems to have existed on its ruins in the reign of Claudius; and the last notice we have of Nineveh in the classics is in Tacitus.

The fanciful history related by Ctesias is now found to be based on distorted Graeco-Persian traditions; and though the writer managed to make the ancient world give credit to him in preference to Herodotus, his work is now proved to be very untrustworthy. According to him, for thirty generations after Ninyas the kings led a life of luxury and indolence in their palace; the last of them, Sardanapalus, made a vigorous defence against Arbaces, the rebel governor of Media, but, finding it impossible to defend Nineveh, he set fire to his palace, and burned himself with all his treasures. This event took place 1306 years after Ninus. Now, the above account represents Nineveh to have perished nearly three centuries before the real date, which was about B.C. 606, and is utterly incompatible with Scripture. Herodotus assigns to the Empire a duration of 520 years, and Berosus of 526. In order to reconcile these conflicting accounts, historians have supposed that Nineveh was twice destroyed, but this supposition is now generally rejected. However, that part of Nineveh was actually destroyed by fire is proved by the condition of the slabs and statues found in its ruins, which show the action of intense heat.

Bibliography. For Assyrian archæology, see the works of Layard, Oppert, and Smith; Perrot and Chipiez, Chaldée et Assyrie (Eng. trans. 1884). For the religion, see Sayce, Assyria (1885); Robertson Smith, Religion of the Semites (1888); Tiele, Comparative Hist. of Relig. (Eng. trans. 1884); Sayce, Hibbert Lectures (1887). For the language and literature, [p. 145] see Delitszch, Assyrische Grammatik (Eng. trans. by Kennedy, 1889); id. Assyrisches Wörterbuch, vols. i.-iii. (1887); Peiser, Keilinschriftliche Bibliothek (1890); Sayce, Lectures on the Syllabary and Grammar (1877). For the history, see Rawlinson, The Five Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World, 4 vols. (1862-67); Oppert, Histoire des Empires de Chaldée et d'Assyrie (1865); Lenormant, Manuel d'Histoire Ancienne de l'Orient, 3 vols. (1869); Ménant, Annales des Rois d'Assyrie (1874); Maspero, Histoire Ancienne des Peuples de l'Orient (4th ed. 1883); Sayce, Ancient Empires of the East (1884); id. Fresh Light from the Ancient Monuments (1886); Maspero, Life in Ancient Egypt and Assyria (Eng. trans. 1892). (Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1898)