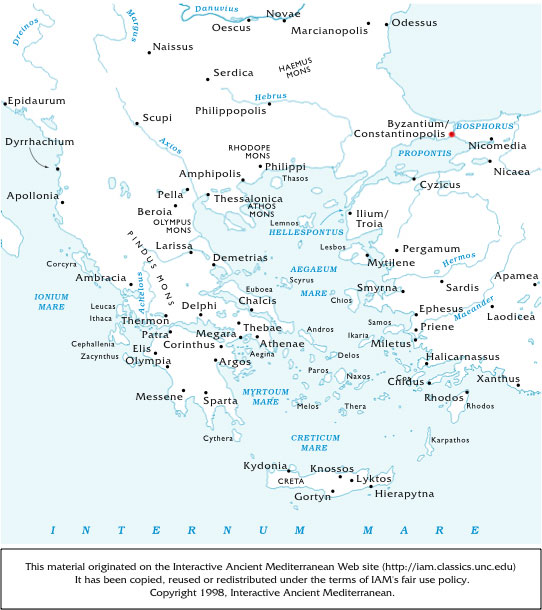

A celebrated city of Thrace, on the shore of the Thracian Bosporus, called at a later period Constantinopolis, and made the capital of the Eastern Empire of the Romans. It was founded by a Dorian colony from Megara, or, rather, by a Megarian colony in conjunction with a Thracian prince. For Byzas, whom the city acknowledged, and celebrated in a festival as its founder, was, according to the legend, a son of Poseidon and Ceroëssa the daughter of Io, and ruled over all the adjacent country. The early commerce of Megara was directed principally to the shores of the Propontis, and this people had founded Chalcedon seventeen years before Byzantium, and Selymbria even prior to Chalcedon ( Herod.iv. 144). When, however, their trade was extended still farther to the north, and had reached the shores of the Euxine, the harbour of Chalcedon sank in importance, and a commercial station was required on the opposite side of the strait. This station was Byzantium. The appellation of "blind men" given to the Chalcedonians by the Persian general Megabazus ( Herod.iv. 144), for having overlooked the superior site where Byzantium was afterwards founded, does not therefore appear to [p. 235] have been well merited. As long as Chalcedon was the northernmost point reached by the commerce of Megara, its situation was preferable to any offered by the opposite side of the Bosporus, because the current on this latter side runs down from the north more strongly than it does on the side of Chalcedon, and the harbour of this city, therefore, is more accessible to vessels coming from the south. On the other hand, Byzantium was far superior to Chalcedon for the northern trade, since the current that set in strongly from the Euxine carried vessels directly into the harbour of Byzantium, but prevented their approach to Chalcedon in a straight course (Polyb. iv. 43). The harbour of Byzantium was peculiarly favoured by nature, being deep, capacious, and sheltered from every storm. From its shape, and the rich advantages thus connected with it, the harbour of Byzantium obtained the name of Chrysoceras, or "the Golden Horn," which was also applied to the promontory or neck of land that contributed to form it. And yet, notwithstanding all these advantages, Byzantium remained for a long time an inconsiderable town. The declining commerce of Megara, and the character which Byzantium still sustained of being a half-barbarian place, may serve to account for this.At a subsequent period, the Milesians sent hither a strong colony, and so altered for the better the aspect of things that they are regarded by some ancient writers as the founders of the city itself. When, at a later day, the insurrection of the Asiatic Greeks had been crushed by Darius, and the Persian fleet was reducing to obedience the Greek cities along the Hellespont and the Propontis, the Byzantines, together with a body of Chalcedonians, would not wait for the coming of the Persians, but, leaving their habitations, and fleeing to the Euxine, built the city of Mesembria on the upper coast of Thrace ( Herod.vi. 33). The Persians destroyed the empty city, and no Byzantium for some time thereafter existed. This will explain why Seylax, in his Periplus, passed by Byzantium in silence, while he mentions all the Grecian settlements in this quarter, and among them even Mesembria itself.

Byzantium reappeared after the overthrow of Xerxes, some of the old inhabitants having probably returned; and here Pausanias, the commander of the Grecian forces, took up his quarters (B.C. 479). He gave the city a code of laws, and a government modelled, in some degree, after the Spartan form, and hence he was regarded by some as the true founder of the city. The Athenians succeeding to the hegemony, Byzantium fell under their control, and received so many important additions from them that Ammianus Marcellinus, in a later age, calls it an Attic colony (xxii. 8). The city, however, was a Doric one, in language, customs, and laws, and remained so even after the Athenians had the control of it. The maintenance of this military post became of great importance to the Greeks during their warfare with the Persians in subsequent years, and this circumstance, together with the advantages of a lucrative and now continually increasing commerce, gave Byzantium a high rank among Grecian cities. After Athens and Sparta had weakened the power of each other by national rivalry, and neither could lay claim to the empire of the sea, Byzantium became an independent city, and turned its whole attention to commerce. Its strong situation enabled it, at a subsequent period, to resist successfully the arms of Philip of Macedon; nor did Alexander, in his eagerness to march into Asia, make any attempt upon the place. It preserved also a neutral character under his successors. The great evil to which the city of Byzantium was exposed came from the inland country, the Thracian tribes continually making incursions into the fertile territory around the place, and carrying off more or less of the products of the fields. The city suffered severely also from the Gauls, being compelled to pay a yearly tribute amounting at least to eighty talents.

After the departure of the Gauls it again became a flourishing place, but its most prosperous period was during the Roman sway. It had thrown itself into the arms of the Romans as early as the war against the younger Philip of Macedon, and enjoyed from that people not only complete protection, but also many valuable commercial privileges. It was allowed, more over, to lay a toll on all vessels passing through the straits--a thing which had been attempted before without success--and this toll it shared with the Romans. But the day of misfortune at length came. In the contest for the Empire between Severus and Niger, Byzantium declared for the latter, and stood a siege in consequence which continued long after Niger's overthrow and death. After three years of almost incredible exertions the place surrendered to Severus. The few remaining inhabitants whom famine had spared were sold as slaves, the city was razed to the ground, its territory given to Perinthus, and a small village took the place of the great commercial emporium. Repenting soon after of what he had done, Severus rebuilt Byzantium, and adorned it with numerous and splendid buildings, which in a later age still bore his name; but it never recovered its former rank until the days of Constantine. Constantine had no great affection for Rome as a city, nor had the inhabitants any great regard for him. He felt the necessity, moreover, of having the capital of the Empire in some more central quarter, from which the movements of the German tribes on the one hand, and those of the Persians on the other, might be observed. He long sought for such a locality, and believed at one time that he had found it in the neighbourhood of the Sigaean promontory, on the coast of Troas. He had even commenced building here when the superior advantages of Byzantium as a centre of empire attracted his attention, and he finally resolved to make this the capital of the Roman world. For a monarchy possessing the western portion of Asia and the largest part of Europe, together with the whole coast of the Mediterranean Sea, nature herself seemed to have destined Byzantium as a capital.

Constantine's plan was carried into rapid execution (A.D. 330). The ancient city had possessed a circuit [p. 236] of forty stadia, and covered merely two hills, one close to the water, on which the Seraglio at present stands, and another adjoining it, and extending towards the interior to what is now the Besestan, or great market. The new city, called Constantinopolis, or "City of Constantine," was three times as large, and covered four hills, together with part of a fifth, having a circuit of somewhat less than fourteen geographical miles. Every effort was made to embellish this new capital of the Roman world: the most splendid edifices were erected, including an imperial palace, numerous residences for the chief officers of the court, churches, baths, a hippodrome; and inhabitants were procured from every quarter. Its rapid increase called, from time to time, for a corresponding enlargement of the city, until, in the reign of Theodosius II., when the new walls were erected (the previous ones having been thrown down by an earthquake), Constantinople attained to the size which it at present has. Chalcondylas supposes the walls of the city to be 111 stadia in circumference; Gyllius, about 13 Italian miles; but, according to the best modern plans of Constantinople, it is not less than 19,700 yards. The number of gates is twentyeight--fourteen on the side of the port, seven towards the land, and as many on the Propontis. The city is built on a triangular promontory, and the number of hills which it covers is seven. Besides the name of Constantinopolis (Kônstantinou polis), this city had also the more imposing one of New Rome (Nea Rhômê), which, however, gradually fell into disuse. According to some, the peasants in the neighbourhood, while they repair to Constantinople, say in corrupt Greek that they are going es tam bolin (i.e. es tan polin), "to the city," whence has arisen the Turkish name of the place, Stamboul. Constantinople was taken by the Turks under Mohammed II. on the 29th of May, A.D. 1453. (Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1898)