An island of the Aegean, situated nearly in the centre of the Cyclades (q.v.). This island was called also Asteria, Pelasgia, Chlamydia, Lagia, Pyrpilis, Scythias, Mydia, and Ortygia. It was named Ortygia from ortux, "a quail," and Lagia from lagôs, "a hare," the island formerly abounding with both these creatures. On this account, according to Strabo, it was not allowed to have dogs at Delos, because they destroyed the quails and hares. The name Delos was commonly derived from dęlos, "manifest," in allusion to the island having floated under the surface of the sea until made to appear and stand firm by order of Poseidon. This was done for the purpose of receiving Leto, who was on the eve of delivery, and could find no asylum on the earth, Heré having bound it by an oath not to receive her; but as Delos at the time was floating beneath the waters, it was freed from the obligation. Once fixed in its place, it continued, according to popular belief, to remain so firm as even to be unmoved by the shocks of an earthquake. This, however, is contradicted by Thucydides and Herodotus, who report that a shock was felt there before the Peloponnesian War ( Thuc.ii. 8; Herod.vi. 98).Delos was celebrated as the natal island of Apollo and Artemis, and the solemnities with which the festivals of these deities were observed there never failed to attract large crowds from the neighbouring islands and the continent. Among the seven wonders of the world was an altar at Delos which was made of the horns of animals. Tradition reported that it was constructed by Apollo with the horns of deer killed in hunting by his sister Artemis. Plutarch says he saw it, and he speaks of the wonderful interlacing of the horns of which it was made, no cement nor bond of any kind being employed to hold it together. Portions of this altar are identified by archćologists in the scattered blocks of marble lately found in the so-called Hall of the Bulls, to the east of the great temple, and named from its "taurine" capitals representing recumbent bulls. The Athenians were commanded by an oracle, in the time of Pisistratus, to purify Delos, which they did by causing the dead bodies which had been buried there to be taken up and removed from all places within view of the temple. In the sixth year of the Peloponnesian War, they, by the advice of an oracle, purified it anew by carrying all the dead bodies to the neighbouring island of Rhenaea, where they were interred. After having done this, in order to prevent its being polluted in the time to come, they published an edict that for the future no person should be suffered to die, nor any woman to be brought to bed, in the island, but that, when death or parturition approached, they should be carried over into Rhenaea. In memory of this purification, it is said, the Athenians instituted a solemn quinquennial festival. See Delia.

When the Persian armament, under Datis and Artaphernes, was making its way through the Grecian islands, the inhabitants of Delos left their rich temple, with its treasures, to the protection of its tutelary deities, and fled to Tenos. The fame of the sanctuary, however, saved it from spoliation. The Persians had heard that Delos was the birthplace of two deities who corresponded to those who held the foremost rank in their own religious [p. 480] system--the sun and moon. This comparison was probably suggested to them by some Greek who wished to save the temple. If we may credit the tradition which was current in the days of Herodotus, Delos received the highest honours from Datis. He would not suffer his ships to touch the sacred shore, but kept them at the island of Rhenaea. He also sent a herald to recall the Delians who had fled to Tenos, and offered sacrifice to the god, in which 300 talents of frankincense are said to have been consumed ( Herod.vi. 97).

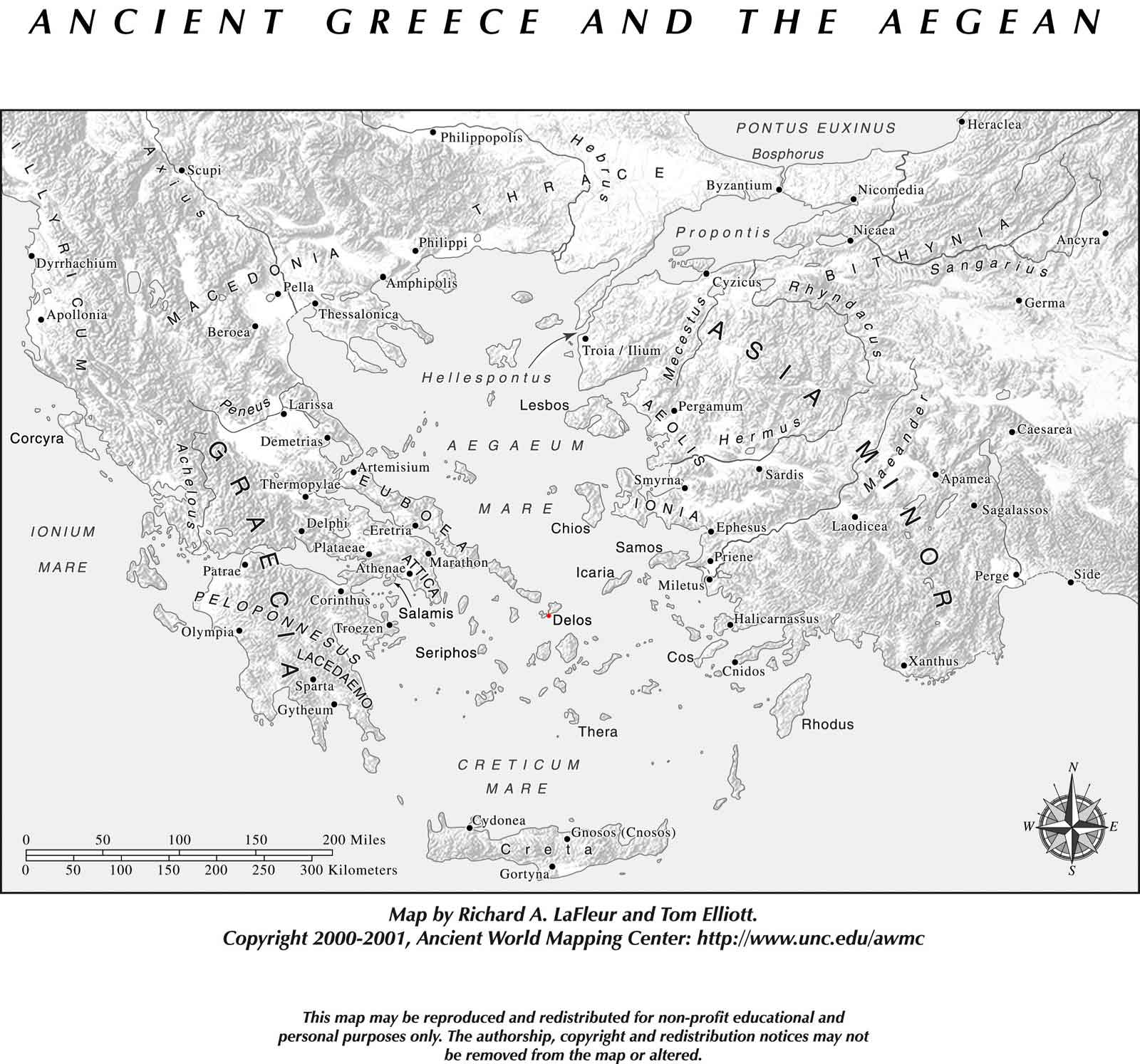

After the Persian War, the Athenians established at Delos the treasury of the Greeks, and ordered that all meetings relative to the confederacy should be held there ( Thuc.i. 96). In the tenth year of the Peloponnesian War, not being satisfied with the purifications which the island had hitherto undergone, they removed its entire population to Adramyttium, where they obtained a settlement from the Persian satrap Pharnaces ( Thuc.v. 1). Here many of these unfortunate Delians were afterwards treacherously murdered by order of Arsaces, an officer of Tissaphernes ( Thuc.viii. 108). Finally, however, the Athenians restored those that survived to their country after the battle of Amphipolis, as they considered that their ill success in the war proceeded from the anger of the god on account of their conduct towards this unfortunate people ( Thuc.v. 32). Strabo says that Delos became a place of great commercial importance after the destruction of Corinth, as the merchants who had frequented that city then withdrew to this island, which afforded great facilities for carrying on trade on account of the convenience of its port, and its advantageous situation with respect to the coasts of Greece and Asia Minor, as well as from the great concourse of people who resorted thither at stated times. It was also very famous for its bronze. The Romans especially favoured the interests of the Delians, though they had conceded to the Athenians the sovereignty of the island and the administration of the temple (Polyb. xxx. 18). But on the occupation of Athens by the generals of Mithridates, they landed troops in Delos and committed the greatest devastations there in consequence of the inhabitants refusing to espouse their cause (B.C. 87). After this calamity it remained in an impoverished and deserted state. The town of Delos was situated at the foot of Mount Cynthus, in a plain watered by the little river Inopus, and by a lake called Trochoeides by Theognis and Herodotus. Remains of the great temple of Apollo, of the temple of Leto, a theatre, a private house, and of several porticoes are among the antiquities that are now visible. Since 1877, M. Homolle and others, on behalf of the French Archćological Institute, have prosecuted very extensive investigations on the site of the town. See Sallier, Hist. de l'Isle de Délos, in the Mém. de l'Académie des Inscriptions iii. 376; and Homolle, Fouilles de Délos (Paris, 1878). (Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1898)