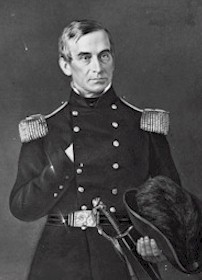

Robert Anderson (1805-1871)

Robert Anderson (June 14, 1805 - October 26, 1871) was a Union Army officer in the American Civil War, known for his command of Fort Sumter at the start of the war. He is often referred to using his rank of that time, Major Robert Anderson.

Robert Anderson was born on June 14, 1805 near Louisville, Kentucky into a slave-holding family steeped in American military tradition. He graduated from from West Point in 1825 (5th out of 37). His brother, Richard, was a lawyer, politician, and diplomat.

Robert Anderson was born on June 14, 1805 near Louisville, Kentucky into a slave-holding family steeped in American military tradition. He graduated from from West Point in 1825 (5th out of 37). His brother, Richard, was a lawyer, politician, and diplomat.

Anderson, after graduating from West Point, served briefly as his brother's private secretary when he was minister to Colombia. He was assigned to further instruction at the Fortress Monroe Artillery School, and then taught Artillery at West Point for two years. Among his students were Sherman, Bragg, Beauregard (who became his assistant), McDowell, Meade, Hooker, and Early.

His first combat experience came when he commanded Illinois volunteers in the Blackhawk Indian wars. As a colonel of Illinois volunteers, where he had the unusual distinction of twice mustering Captain Abraham Lincoln out and in of army service. At the Battle of Bad Axe on August 3, 1832, he saved the saved an infant Indian from its mother's arms, wounded by the bullet which had killed its mother, and brought it to a dressing station. Three days later he wrote in disgust to his brother that he had observed scenes of "misery axceeding any I ever expected to see in our happy land. Dead bodies, males & females, strewed along the road, left unburied, exposed—poor, emaciated beings."

Returning to the U.S. Army as a first lieutenant in 1833, he served in 1837 in the Second Seminole War, as an assistant adjutant general on General Winfield Scott's staff. He contracted fevers which recurred for the rest of his life. Because of the illness he could have excused himself from the Mexican War, but he offered to serve anyway, declining an offer to serve on Scott's staff. He was severely wounded at the battle of Molino del Rey, for which he received a brevet promotion to major. Halfway through the war he wrote to his wife, Eba (whom he had married in 1842, Winfield Scott standing in for her father): "I think that no more absurd scheme could be invented for settling national difficulties than the one we are ingaged in—killing each other to find out who is in the right."

After his service in Florida, Anderson had, with the exception of the interlude in Mexico, worked in administration. In 1839 he translated a French manual on artillery (Instruction for Field Artillery, Horse and Foot), clarifying the text and adding illustrations. This established Anderson as an authority on the subject. One result was that the American artillery became more efficient, more mobile, thus contributing to the defeat of the Mexicans a few years later.

After the Mexican War he became a member of the commision which in 1851 produced the US army's official textbook for siege artillery. From 1855 to 1859, in view of his precarious health and probably also due to his connections to Winfield Scott, he was assigned to the light duty of inspecting the iron beams produced in a mill in Trenton, New Jersey for Federal construction projects. He eventually received a permanent promotion to major of the 1st U.S. Artillery in the Regular Army on October 5, 1857.

In the fall and summer of 1860, Anderson was a member of a commission which, along with his friend Senator Jefferson Davis, examined the curriculum of West Point and its system of discipline. At the time he was 57 and considering retirement, and he would normally have passed into contented obscurity. However, on November 15,1860, he received an order: "Major Robert Anderson, First Artillery, will forthwith proceed to Fort Moultrie, and immediately relieve Bvt. Col. John Gardner, lieuteant-colonel of First Artillery, in command thereof."

The order, although signed by General Winfield Scott, emanated from the office of the Secretary of War and future Confederate General John B. Floyd who probably chose Anderson in light of his supposed Southern sympathies. Because of his background, and because he had married the daughter of a wealthy Georgia slave holder, but without much other justification, as he was a quiet and reticent man, Anderson was considered pro-southern and a defender of slavery. It is true that he, through his marriage, had become the owner of a small number of slaves, but he sold them all shortly before the beginning of the Civil War. In any case, it was expected that he would be cautious and tactful in his duties, thereby avoiding actions provocative to South Carolina. Southerners as well thought Anderson would be sympathetic to their demands that the forts be turned over to the Confederacy. Indeed, Anderson himself seemed to think that if war could be avoided, the seceding states might, ultimately, return peaceably to the Union. However, apparently nobody had counted on his rigid concept of duty. He liked to say that he lived by his father's religion and General Washington's politics, and that he needed only three documents to guide his path: the Ten Commandments, the Constitution, and the book of army regulations, and he apparently threw in his lot with the Union without hesitation. Through his resolution and patience he made an essential contribution to the Union war effort by getting Beauregard to fire first.

Given little assistance by the Buchanan Administration, Anderson was greatly perturbed by having to choose between war and peace. He took matters into his own hands on December 26, following the secession of the state six days earlier, when he moved his two-company garrison from barely defensible Fort Moultrie to unfinished Fort Sumter in the middle of the harbor. Decades in the building, it was a large and solid structure of concrete slabs erected on an artificial island overlooking the seaward approaches to Charleston. During this entire period he had had no specific instructions from the administration in Washington. Secretary of War Floyd did send to him Don Carlos Buell, then a captain attached to the War Department, with memorized verbal instructions which Buell, after having seen the condition of Ft. Moultrie, then interpreted in a manner which left Anderson some leeway to decide for himself, whether to transfer or not to Sumter. Taking advantage of the holiday season and reduced surveillance on the part of the South Carolina milita, Anderson carried out the move during the early evening of December 26, 1860, thus embarrassing President Buchanan and inflaming Southern public opinion.

After the unannounced relief ship Star of the West was fired upon by Carolinian gunners on January 9, 1861, Anderson, not wishing to start a war, withheld his fire. Fort Sumter now was regarded by people on both sides as a symbol. After Lincoln took office, many in his cabinet were willing to relinquish it, but not Lincoln. The Charleston Mercury wrote: "Let us be ready for war . . . Border Southern States will never join us until we have indicated our power to free ourselves—until we have proven that a garrison of seventy men cannot hold the portal of our commerce. The fate of the Southern Confederacy hangs by the ensign balliards of Fort Sumter."

By April 5, General Beauregard had deprived the fort of its daily supply of food from Charleston and made repeated demands that Anderson surrender, which he refused. On April 12, 1861, just as a relief expedition of several ships was approaching, the Confederates opened fire. The opening bombardment of the Civil War lasted 2 days. On April 14, 1861 Anderson formally surrendered after his food and ammunition had run out.

On April 18, 1861 he sent a dispatch after boarding the steamship Baltic: "Having defended Fort Sumter for thirty-four hours, until the quarters were entirely burned, the main gates destroyed by fire, the gorge walls seriously injured, the magazine surrounded by flames, and its door closed from the effects of heat, four barrels and three cartridges of powder only being available, and no provisions remaining but pork, I accepted terms of evacuation offered by General Beauregard, being the same offered by him on the 11th instant, prior to the commencement of hostilities, and marched out of the fort Sunday afternoon, the 14th instant, with colors flying and drums beating, bringing away company and private property, and saluting my flag with fifty guns."

Thanks to the solid structure of the fort, he suffered not a single casualty during the bombardment, thus demonstrating the wisdom of his decision to abandon Fort Moultrie. He returned to the North with his garrison and, despite a hero's welcome, felt a sense of failure in not having prevented the war.

Anderson took the fort's 33-star flag with him to New York City, where he participated in a Union Square patriotic rally that is thought to have been the largest public gathering in North America up to then.

Anderson was promoted to Brig. Gen. USA on May 15, 1861, and took command of the Department of Kentucky on May 28, 1861. On August 15, 1861 the department was renamed Department of the Cumberland. He was at first based in Cincinatti, from where he began recruiting, but transferred to Louisville shortly after the Confederate General Leonidas Polk (without orders) moved into Kentucky and occupied Columbus on the Mississippi. This act violated the precarious neutrality declared by the Kentucky state government, and thus provided Anderson with an excuse to transfer his headquarters to Louisville. He started his assignment with no troops and no equipment, but he had the foresight to insist upon having the services of George H. Thomas and to put him in charge of Fort Dick Robinson, the nation's first modern basic training camp. He worked to get Thomas supplies and to get him promoted.

Perhaps weakened by the mental and physical demands of his Sumter service and by the enormous difficulties of his new assignment, he relinquished command on October 8, 1861. Afterward he went to Washington and supported Thomas as best he could, intervening to keep him from being replaced by a political general.

Anderson retired from the army due to disabilities on October 27, 1863, and was breveted Maj. Gen. USA on February 3, 1865.

Days after Robert E. Lee's surrender and the effective conclusion of the war, Anderson returned to Charleston and, four years to the day after lowering the 33-star flag in surrender, raised it in triumph over the recaptured but badly battered Fort Sumter during ceremonies there. Ironically, that same evening, April 14, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated.

He later went to Nice, France, seeking a cure for his ailments, and died there on October 26, 1871. He is buried at the West Point National Cemetery.

Robert Anderson was born on June 14, 1805 near Louisville, Kentucky into a slave-holding family steeped in American military tradition. He graduated from from West Point in 1825 (5th out of 37). His brother, Richard, was a lawyer, politician, and diplomat.

Robert Anderson was born on June 14, 1805 near Louisville, Kentucky into a slave-holding family steeped in American military tradition. He graduated from from West Point in 1825 (5th out of 37). His brother, Richard, was a lawyer, politician, and diplomat.